In brief: Has the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season been a bust? In short, no. However, we are enjoying a rare period of quietude in late August, and with temperatures incredibly warm in the Gulf of Mexico at present we’ll take it. To get a better idea of what’s going on, and to understand why September is likely to be active, we are sharing this post which was originally published by The Eyewall this morning.

Forecasts called for an incredibly active season

Coming into this hurricane season, there were breathless forecasts calling for anywhere from 20 to even 30 named storms from some folks. Government forecasts were more conservative but even they were the most active we’ve ever seen from NOAA. Colorado State, too. So, as we sit here on August 21st with next to nothing showing up in modeling for the next 7 to 10 days, it’s reasonable for the general public to ask questions about those forecasts.

Back on day one of hurricane season this year, The Eyewall published a piece about ways this hurricane season could essentially fail, or at least turn out “less bad.” We advertise ourselves as no hype, which as comments occasionally show has good elements and bad elements (we seriously thank you all for your support and readership—and constructive feedback only helps us to do better!). But the question was basically “Are we overhyping this season?” And the answer was no: All the elements that you would want in place for a historically active season were in place. All those big time forecasts were justified.

Where are the storms?

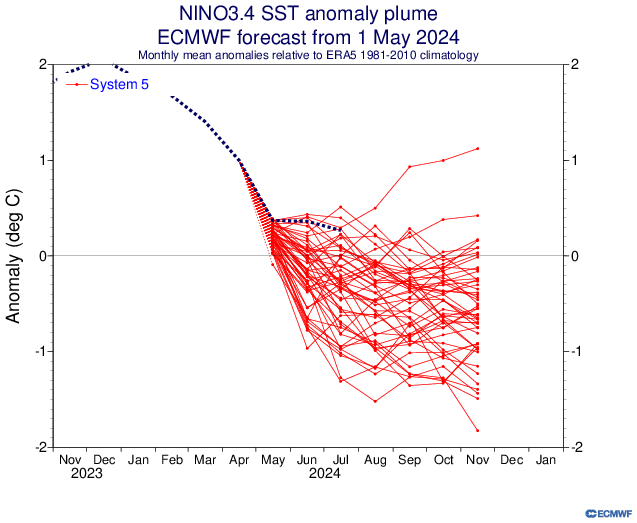

One of our potential fail modes was if La Niña developed too slowly. Indeed, the pace of the La Niña development this season, while uneven, has generally lagged the strongest projections. At least officially. Here’s a look at the May 1st European model ensemble outlook for the ENSO 3.4 region, the box of temperatures we look at to basically designate La Niña or El Niño.

We should begin closing in on an official La Niña designation in the next month or two, but we aren’t quite there yet. Keep in mind, this is by no means a perfect representation of things, and sometimes the atmosphere can behave more Niña-like even if we aren’t officially there yet. But this has not developed as aggressively as some modeling showed in developing in spring.

So, at a very, very distant level, perhaps that has something to do with it. Michael Lowry, in his excellent daily newsletter pointed out yesterday that wind shear has become almost too extremely reversed this month. Typically, during a La Niña, there is more of an easterly component from the wind that counteracts or reduces the usual west to east winds that can cause shear in the Atlantic, detrimental to hurricane development. In a twist of fate, there’s so much of an easterly component to the upper level winds this year that it’s actually causing easterly shear. Otherwise, we might be a good bit busier at the moment. If you look at the basin as a whole since June 1st, winds have been generally lighter than usual in the Caribbean and much of the Atlantic and a bit stronger than usual in the southwest Atlantic and in the Gulf.

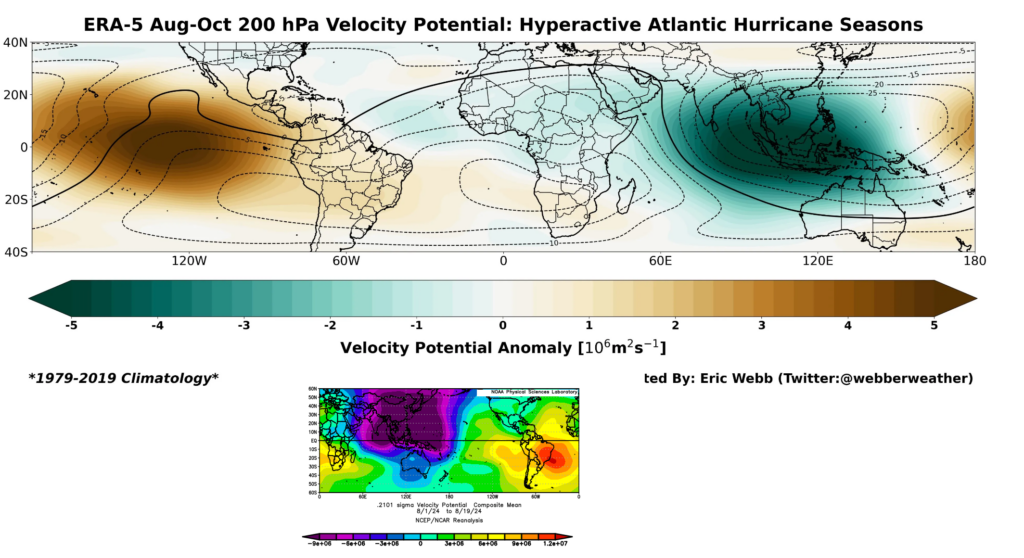

Let’s dig a little deeper. One thing that’s legitimately fascinating to me right now is what’s happening in terms of upper level background support in the atmosphere. Using a variable known as velocity potential, we can see that in historically active hurricane seasons, you would expect to see a significant area of rising air in the Indian Ocean, bleeding a bit into Africa (green on the top map below). Opposite to that, there would be a significant area of sinking air in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (brown colors below). Why is this important? In order to generate an active outbreak of storms in the Atlantic, you need disturbances tracking across Africa, which tend to get supported by rising air over and just east of there. You also prefer to see the Pacific undergoing sinking air, as a way to keep it from ‘robbing’ the favorable conditions for storminess. Sinking air suppresses thunderstorm development and tends to dry out the air a bit.

So what’s going on right now? So far this August, we’ve actually *had* what we would expect from a hyperactive season in the Indian Ocean. Click to enlarge the image below.

We have a ton of rising air in the Indian Ocean this month (purple & blue on the bottom map above). We have that extending into Africa. This is what you’d expect for a busy season. Where it differs, however is exactly where the sinking air (red/orange in the bottom panel above) is located. In a typical hyperactive season, this is focused over the Eastern Pacific. This year, it’s focused on the eastern side of South America. This is Matt speculating wildly here, but: I suspect that we’re seeing the right ingredients in place, but I think we are seeing them out of phase. The rising air in the Indian Ocean extends deeper into the Pacific, and there is more of a neutral Eastern Pacific signal right now. This is helping boost activity in the Pacific.

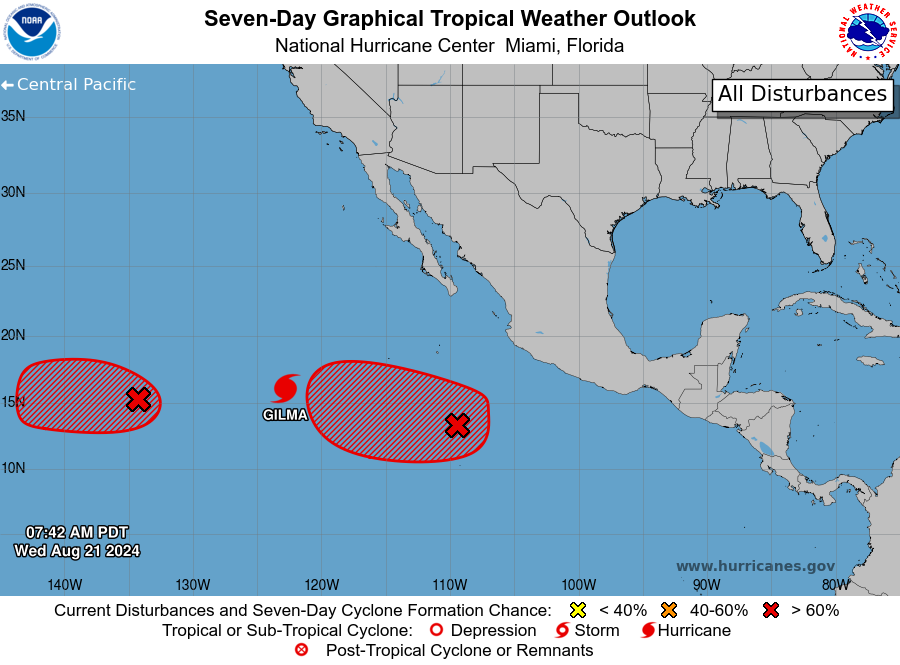

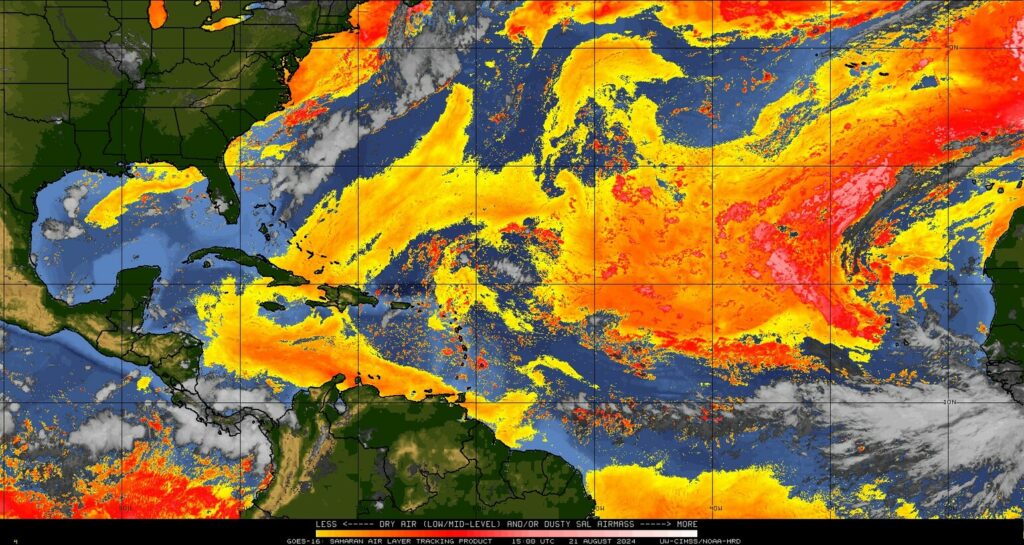

What is in the west will come east

The problem with the tropics is that support like this generally moves from west to east, and eventually this will change. So the quiet now may change in a very, very quick way come September when this (presumably) shifts. For now, the Atlantic is still seeing rampant dust and a slightly displaced intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) which is sending disturbances off Africa too far north and into dust. So they die off earlier. This too will change.

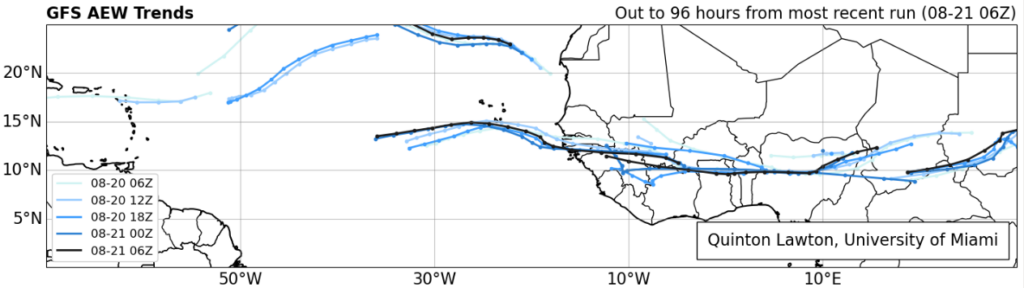

In fact, if you look at the forecast of African Easterly Waves (AEWs) from the latest GFS model, you can see this southward shift approaching heading into the next week or two. The waves lined up over Africa are about 5 to 10 degrees farther south in latitude about 4 days from now, which means they will emerge farther south and in more of a traditional area less exposed to Saharan dust in late August and September.

So, yes, things are almost certainly going to pick up soon.

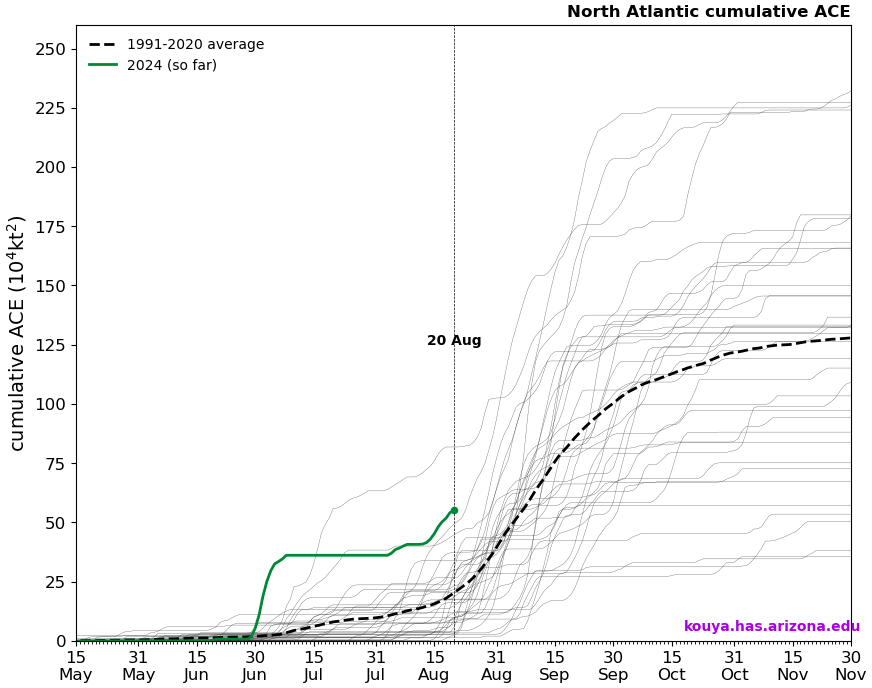

Despite perception, this season’s current accumulated cyclone energy is running nearly 3 times higher than usual! We’ve amassed as much ACE so far this season as we’d typically see by the peak day of hurricane season (September 10th). We’ve done this on the backs of only five storms so far, three of which have been hurricanes, and one of which (Beryl) smashed early season records in the Caribbean and Atlantic.

So despite the perception that this season has been slow to start, it actually has not been. In fact, 2024 is in rarefied air in terms of ACE to date. This perception might have to do with storm inflation, or the idea that we are naming more storms today than we did, say, 20 or 30 years ago. In 2020, basically the benchmark for recent historically active seasons, today marked the formation date for Hurricane Laura, the 12th named storm of the season. Here we are in 2024 sitting at five, and it’s no wonder the perception is skewed. Despite having more than twice as many storms to this point in 2020, we only had half the ACE (26 vs. 55 this year). 2020 kept churning out mostly sloppy storms until Laura, and then things got nasty. We’ve had three legitimate hurricanes this year and only about one “throwaway” storm (Chris). The takeaway message here is that: We can make up ground in September very, very fast. Very fast.

In summary

So, no, this season’s extremely active hurricane seasons have not been a bust so far, and they probably won’t end up being a bust overall. We’ve had a “bang for our buck” season so far with quality storms over quantity as, say, in 2020. And while we are in a lull now, the setup is probably going to change in 7 to 10 days to allow things to crank up in September. Never call it a bust. If it is one, we can discuss why in November. For now, use this quiet time to review your hurricane preparedness plans and supply kits. And stay tuned here for the latest.

I would say that this season has been a wild one already with just Beryl and Debby. Berly was the earliest cat 5 on record and the catastrophic flooding that Hurricane Debby has caused in the northeast. I am a little nervous about what September is going to bring especially since more favorable conditions seem to be ramping up. Proper atmospheric conditions on top of record warm ocean temperatures spells a recipe for disaster.

In Central America, they consider hurricane season to not start until September. And while it didn’t hit, it formed and passed damn close. And possibly did damage they didn’t bother to tell us about here in the U.S. Though I don’t see a follow up to this article: https://www.centralamerica.com/news/hurricane-beryl-threatens-central-america/

We are going Mediterranean cruise 10 days 9/1/24 what are odds we get stuck there with hurricane in Texas

97.6%

Once again, thank you for the insightful analysis. You guys are awesome! I’ve lived in the Houston/Galveston area all my life experiencing every hurricane since Carla in September 1961. September is always volatile so I will never get complacent about what can happen during that month. I won’t relax until Halloween!

You all provide a great service to our community and beyond!

Definitely, no hype, and something for everyone in your blogs from the very basic of facts ask the way deep into the weeds for the weather geeks out there.

And for the folks out there that bash on Eric and Matt when they get it wrong, remember they are “FORECASTING/PREDICTING” what’s going to happen. Even with the amazing amounts of science and data at their disposal, they’re still working with natural forces that can and do bust the best of forecasts!!!

Again, y’all are much appreciated!!!

I don’t like all those ” very fast “ you threw in there.

With air conditioning in our homes and cars, I’m willing to tolerate excessive heat from a high pressure system in August and September if it prevents a hurricane from coming our way. So far the power outages in the aftermath of Beryl were the worst part. Surviving a direct hit from a Category 4 or 5 storm would be a whole different matter.

From a different perspective- why do we live somewhere where we have to choose between the two? That’s what I keep asking myself.

Prior to Beryl, the two biggest wind hurricanes to affect Houston in recent history were in September

Rita: Sept 24, 2005

Ike: Sept 13, 2008

(Harvey was a rain event for Houston, Aug 26-29, 2017)

Whether the 2024 North Atlantic hurricane forecast is a bust or not hardly matters. It only takes one hurricane going the “wrong way” and hitting us to devastate our area.

Rita (Sept 2005) mainly affected traffic leaving Houston ahead of the storm. The storm made landfall in western Cameron Parish (LA) and devastated that area (wind and storm surge) and parts of SE Texas, but not reaching the Houston metro area. I remember clearly because we tried to evacuate to Austin and drove in mind-numbing stop-and-go slow traffic on Hwy 290 for 11 hours, making it nearly to Hempstead. (It didn’t help that I had a vehicle with a clutch and standard transmission.) At that point, with traffic still inching along and very few gas stations open, we decided to return to our home in SW Houston and take our chances with Rita. With no inbound traffic, we made it home in about 40 minutes. The next day we awoke to clear skies. We barely felt any effects from Rita at our house. Houston was on the “good side” of the storm.

Hurricane Alicia (Aug 1983) had a major impact on Houston. It made landfall at San Luis Pass as a Category 3 storm. The eye passed directly over the western part of Houston, including my house. I remember going outside in the calm of the eye early on the morning on Aug 18, and when the winds returned thinking I could easily get struck by something blowing in the 90-mph wind. Alicia blew out many windows in downtown skyscrapers, causing a dangerous environment on the streets below. A journalist friend of mine drove the downtown streets with a city engineer while the glass sheets from tall buildings were falling down all around them. Fortunately they weren’t hurt, but the city changed its building code shortly after.

Rita felled two trees in our back yard and our power was out for 7 days (near Champions area). Maximum 3-second gust at Bush IAH during Rita was 64 mph; maximum 2-minute sustained winds at IAH were 45 mph.

After looking at the ACE chart you included, I went to the cited page (I was looking to identify which lines were 2020 and 2017), and saw that the eastern North Pacific cumulative ACE was as historically low as the North Atlantic was high. Are there any relationships between these trends and are there any additional insights that could be derived by comparing the two?

Great summary! It aint over till its over. 😉

I thought I was having deja-vu … this newest post (August 21, 2024 at 11:24 am) is basically a carbon-copy of the article posted today on The Eyewall. Seems easier to post a link, rather than confuse us retired folks 🙂

Having my nightmare vision again of three or four major hurricanes churning simultaneously in the Gulf as they merge into one monster Cat 5 which flattens everything from Corpus to New Orleans….

We’re here for no-hype, not no-hope. come’on mannnnn.

Thanks for all you do guys. Having said that I think so far this season has been a total bust. We was supposed to have a hurricane season from hell according to many that would make 2005 look tame. If you take Beryl out of the picture of a Cat 5 when it was in the Caribbean this would make the season really a bust. After all only 5 named storms. Now hopefully even though September could get busy all the storms will be fish storms.

I would say that 4 named storms is not anywhere near the activity hype that was reported. The whole thesis on warming and more violent storms is suspect as there are many, many factors, some pointed out here, that determine whether storms form. AGW or climate change hype has surely led to “the very active “ claims and while the world continues to burn Fossil Fuels at record rates the forecasts for more devastating storms are neither accurate nor reasonable. Four named storms by the end of August does not make an active season. Clearly it takes much more than warm water.

I do appreciate the break from the droughts we have had the past two years. I am buying hay at half rated despite wildfires in the panhandle. I will put my first bale out for cows this weekend.