If you’ve lived in Houston–or any other place near a large body of water, for that matter–you’ve heard the term “sea breeze” quite a lot, especially during the summer. We often discuss the sea breeze in relation to those scattered, sometimes intense, thunderstorms we saw pop up over the region since Sunday. But what is a sea breeze, and how does it work?

Braniff Davis

It’s that time of year—so what exactly is the Heat Index?

Here’s the latest edition of Weather whys, a series of posts by Braniff Davis explaining the science behind weather phenomenon affecting Texas.

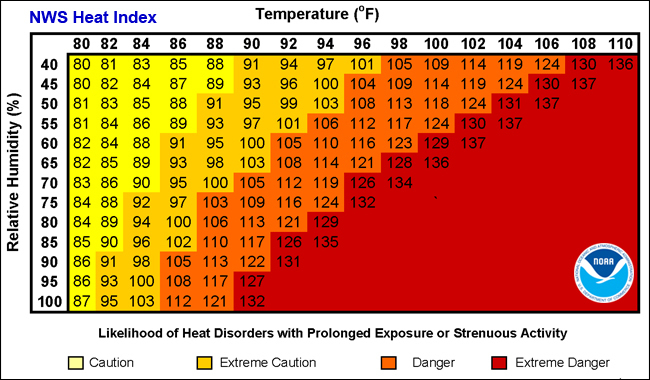

A reader asked us a great question on Eric’s post this morning about the meaning of a heat index. In a place as hot and humid as Houston, we see meteorologists refer to the heat index all the time, saying things like, “The air temperature is 97 degrees, but the humidity makes it feel like 107 degrees outside.” But what does this actually mean?

With heat indices, there’s a little bit of meteorology—and a little bit of perception. The heat index is an ‘apparent temperature,’ or a measure of how hot air actually feels against your skin. When our bodies sweat, that sweat evaporates off of our skin into the atmosphere. This evaporation of moisture releases latent heat away from the body and, in turn, cools you down. However, when there is already a lot of moisture in the air, the sweat doesn’t evaporate as easily. This makes it harder for our bodies to cool, and therefore, the temperature you feel on your skin is much hotter than the actual air temperature.

HOW DO WE KNOW HOW HOT IT FEELS?

Why weren’t the storms last week considered tropical systems?

This is the latest edition of Weather whys, a series of posts by Braniff Davis explaining the science behind weather phenomenon affecting Texas.

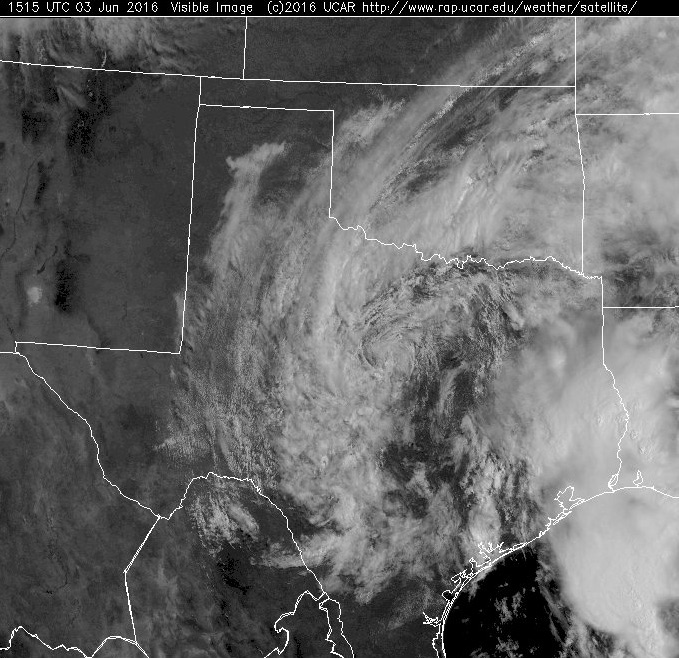

Now that we’ve enjoyed a few sunny days after an extremely wet May and early June, we wanted to tackle a few ‘weather whys’ questions people have asked, either on Facebook, Twitter, or in the blog comments. One reader asked why the weather system last week, which dumped so much rain on the region, was not considered a ‘tropical system.’ After all the system spun counter-clockwise, and had the satellite appearance of a tropical cyclone.

The answer has to do with how and where different low pressure cyclones form. Pressure, and how it influences weather systems, is vexing. Often, it was the most challenging concept for my students to grasp in my introduction to meteorology classes. We could probably do a 50-part series on the science behind it, called cyclogenesis. For now, we’ll spare you that and only focus on the large, synoptic scale cyclones that influence our weather.

EXTRATROPICAL VS. TROPICAL CYCLONES

Two days, two immense Texas storms

Reminder: Braniff Davis, who is finishing a master’s degree in meteorology from San Jose State University, has joined Space City Weather as a contributor. He will be moving to Houston soon, and he will help explain the why’s of Houston’s weather, and will also be tracking air quality and related issues for the site. Please welcome him and feel free to give him a follow on Twitter!

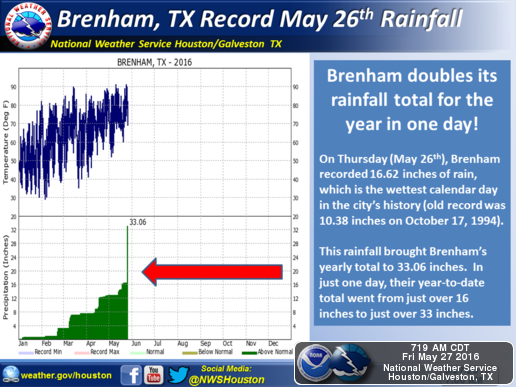

While people inside the loop didn’t get to experience Thursday’s deluge, it was truly unprecedented–especially for the weather station in Brenham, which measured an astounding 16.62 inches of rain:

To give you an idea of how much rain that is, consider this: since July 1, 2015, San Jose State University, where I currently work, has recorded 16.02 inches of rain–in an El Niño year!

Fast forward 24 hours later, and the region felt like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day. Another system, though faster moving and not as intense, flooded the northern metro region once again on Friday. What caused these intense, long-lasting storms?

MESOSCALE CONVECTIVE SYSTEMS

The region experienced so much rain thanks to what’s called a backbuilding mesoscale convective system. Below is a GOES-13 satellite infrared video of Thursday’s system, from Dan Lindsey:

Let’s break down the science behind these massive storm systems. A mesoscale convective system (MCS) is a large, organized, slow moving group of thunderstorms. These storms are largely seasonal–for Texas, most MCS events occur in May & June. Inside the MCS, several thunderstorms are developing and dissipating at the same time. Tropical, moist air, moving northward from the Gulf in a low-level jet stream, provides the energy the system needs to survive and persist for several hours. Eventually, the system dies down, usually overnight–but it can leave behind moisture and atmospheric vorticity (essentially areas of “spin” in the atmosphere), which can actually cause future thunderstorm outbreaks if the atmosphere remains unstable. This is why, on Friday, another MCS flooded the region:

The backbuilding of the MCS development is the reason why these storms appear to stop moving, or move very slowly. Backbuilding occurs when thunderstorms begin to form behind other thunderstorms, upstream of the storm’s motion. It is often caused by the outflow boundary, or gust front, providing the lift needed to create more convection. This also acts to slow the forward movement of the MCS. You can see this backbuilding in Thursday night’s radar loop:

A line of thunderstorms continually builds “backwards” from east to west, between The Woodlands and Austin, creating the appearance of a stationary system. Compare this to the thunderstorm approaching from Kerrville (labeled ERV on the left side of the loop) in the more typical west to east pattern. This constant backbuilding leading to repeated rounds of thunderstorms causes “extreme” flash floods associated with MCS events.

In an eerie coincidence, one year ago this past week, the Memorial Day floods were caused by a larger, longer lasting, mesoscale convective system. As we are still in the midst of the MCS “season”, it’s a good idea to stay extra plugged into the forecast when thunderstorms are possible.