Reminder: Braniff Davis, who is finishing a master’s degree in meteorology from San Jose State University, has joined Space City Weather as a contributor. He will be moving to Houston soon, and he will help explain the why’s of Houston’s weather, and will also be tracking air quality and related issues for the site. Please welcome him and feel free to give him a follow on Twitter!

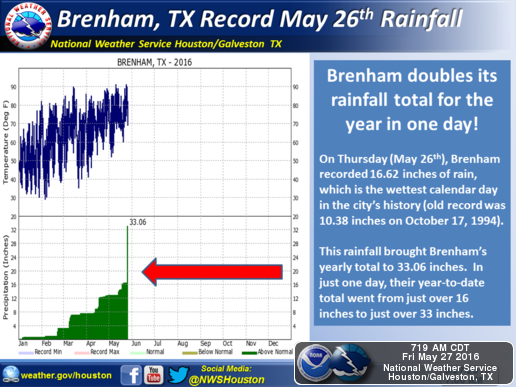

While people inside the loop didn’t get to experience Thursday’s deluge, it was truly unprecedented–especially for the weather station in Brenham, which measured an astounding 16.62 inches of rain:

To give you an idea of how much rain that is, consider this: since July 1, 2015, San Jose State University, where I currently work, has recorded 16.02 inches of rain–in an El Niño year!

Fast forward 24 hours later, and the region felt like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day. Another system, though faster moving and not as intense, flooded the northern metro region once again on Friday. What caused these intense, long-lasting storms?

MESOSCALE CONVECTIVE SYSTEMS

The region experienced so much rain thanks to what’s called a backbuilding mesoscale convective system. Below is a GOES-13 satellite infrared video of Thursday’s system, from Dan Lindsey:

Let’s break down the science behind these massive storm systems. A mesoscale convective system (MCS) is a large, organized, slow moving group of thunderstorms. These storms are largely seasonal–for Texas, most MCS events occur in May & June. Inside the MCS, several thunderstorms are developing and dissipating at the same time. Tropical, moist air, moving northward from the Gulf in a low-level jet stream, provides the energy the system needs to survive and persist for several hours. Eventually, the system dies down, usually overnight–but it can leave behind moisture and atmospheric vorticity (essentially areas of “spin” in the atmosphere), which can actually cause future thunderstorm outbreaks if the atmosphere remains unstable. This is why, on Friday, another MCS flooded the region:

The backbuilding of the MCS development is the reason why these storms appear to stop moving, or move very slowly. Backbuilding occurs when thunderstorms begin to form behind other thunderstorms, upstream of the storm’s motion. It is often caused by the outflow boundary, or gust front, providing the lift needed to create more convection. This also acts to slow the forward movement of the MCS. You can see this backbuilding in Thursday night’s radar loop:

A line of thunderstorms continually builds “backwards” from east to west, between The Woodlands and Austin, creating the appearance of a stationary system. Compare this to the thunderstorm approaching from Kerrville (labeled ERV on the left side of the loop) in the more typical west to east pattern. This constant backbuilding leading to repeated rounds of thunderstorms causes “extreme” flash floods associated with MCS events.

In an eerie coincidence, one year ago this past week, the Memorial Day floods were caused by a larger, longer lasting, mesoscale convective system. As we are still in the midst of the MCS “season”, it’s a good idea to stay extra plugged into the forecast when thunderstorms are possible.

Welcome! Good read.

Thanks and welcome! What a trio! What I like about this site is that I get real information without hype, based on DATA, and an explanation of some of the science behind it. As a scientist, I just love that! I also think there is a real kindness and respect in the way questions are answered.

Thanks for the background. Love theweatherprediction.com site too.

I’ve been following this for a few weeks now. I really appreciate that you give us the science, diagrams and links to sources. Your information helps those of us who want to understand the workings of our weather better, not just spoon feed us what the current educated guesses are. I really enjoy being able to make decisions based on facts and details. I feel like I am getting education from your site… Thank you so very much!!!

It’s absolutely refreshing to get such a science-driven report and forecast. Welcome Braniff!

Nice explanation Braniff, thanks

Wecome to the best of the best weather forecasting. When will El Nino end ? and how many years ’til its return ?

El Nino is actually on its way out now–for all intents and purposes, it won’t really have an impact the rest of the year.

As for the return, it varies. The interval is usually pretty irregular–every two to seven years–and they vary wildly in intensity.

I thought a split in the jet stream played a part in this.

Not necessarily–all you need is upper level divergence.

If you or anyone is interested in the technical information involved with MCS formation, this paper is great: http://www.cims.nyu.edu/~pauluis/Olivier_Pauluis_Homepage/Journal_Club_files/Rev%20Geophys%202004%20Houze.pdf