In brief: Houston faces a wet Labor Day Weekend, but our flooding concerns are clustered primarily along the coast. Mostly cloudy skies will keep a lid on temperatures over the holiday weekend, keeping things dare I say almost comfortable outside most of the time? We are also tracking the tropics as they begin to heat up.

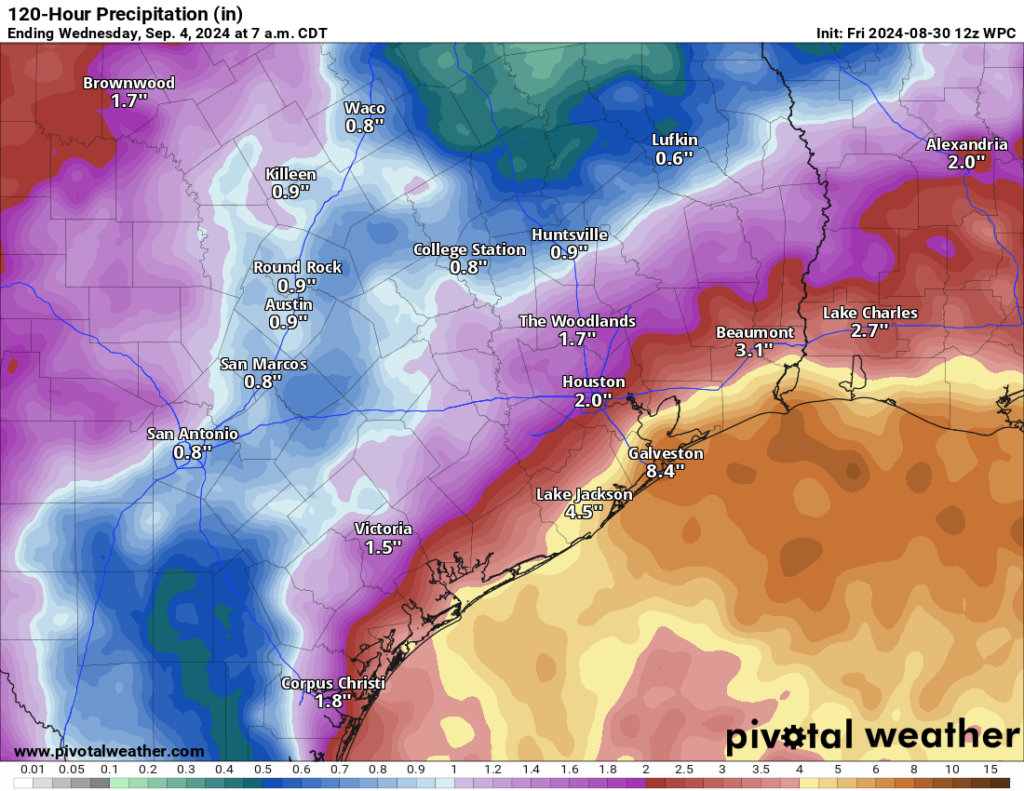

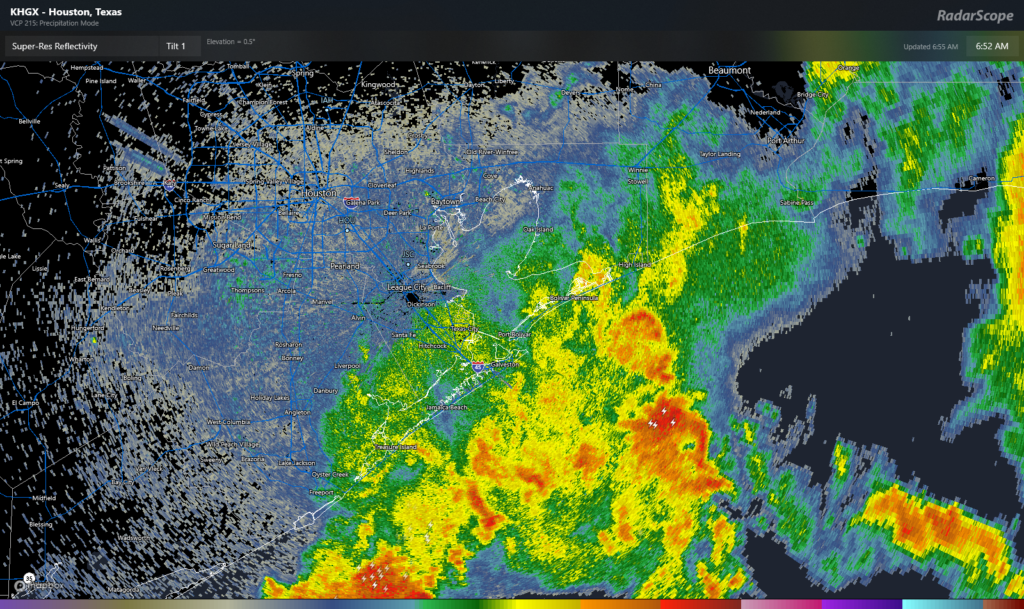

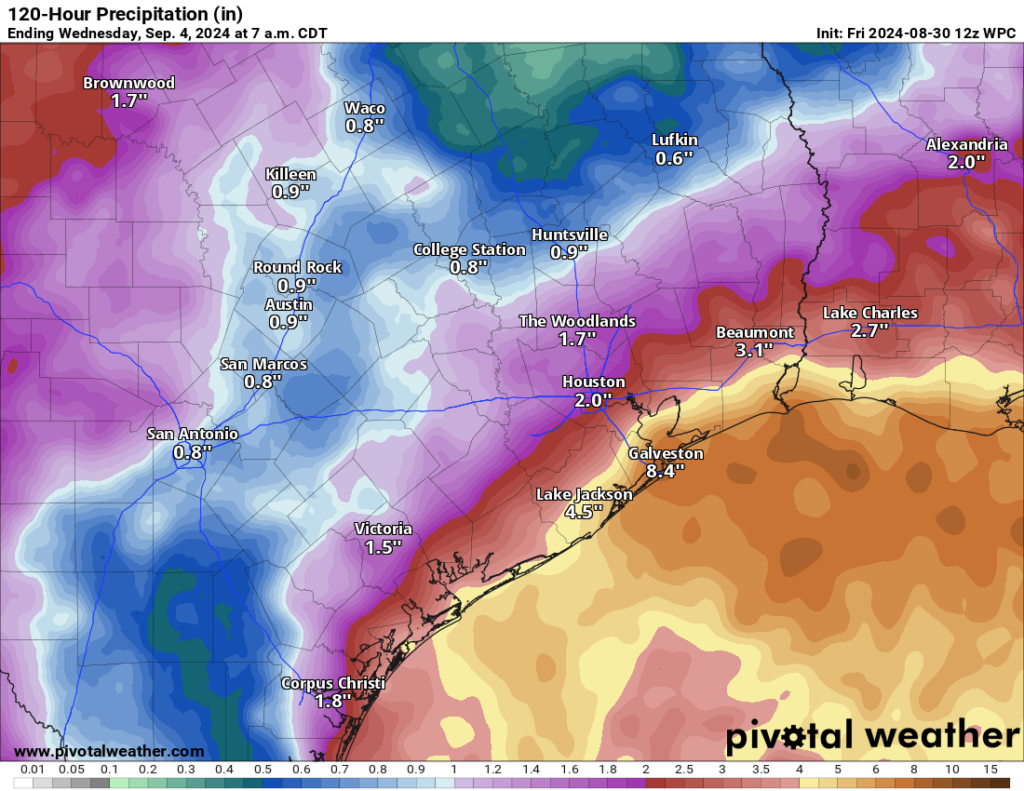

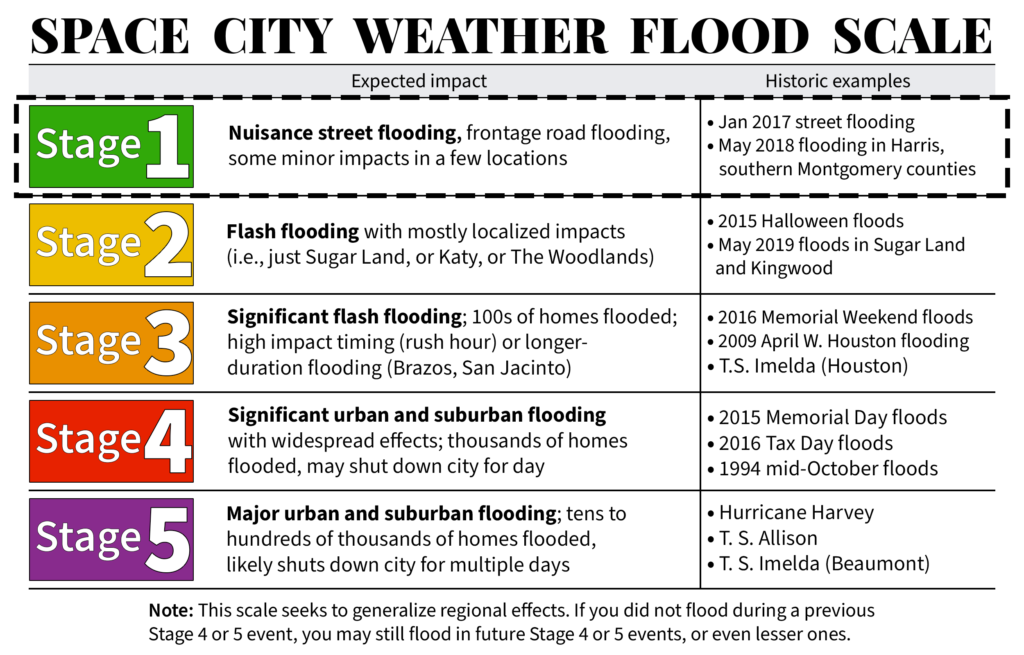

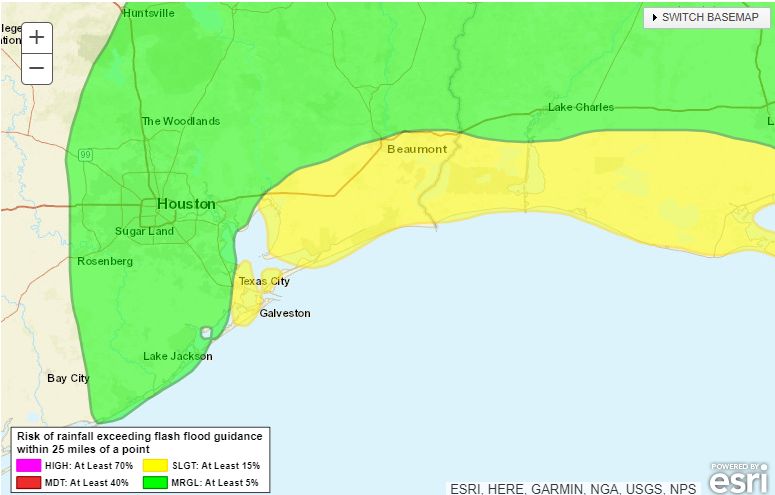

Good morning. We’re providing updates through this weekend on Space City Weather due to the ongoing potential for heavy rainfall through early next week. However, our Stage 1 flood alert remains in effect only for coastal counties, from Galveston County eastward. This is where our modeling continues to indicate the potential for some street flooding over the next several days. For example, here’s where the likelihood of heavy rainfall is greatest for today:

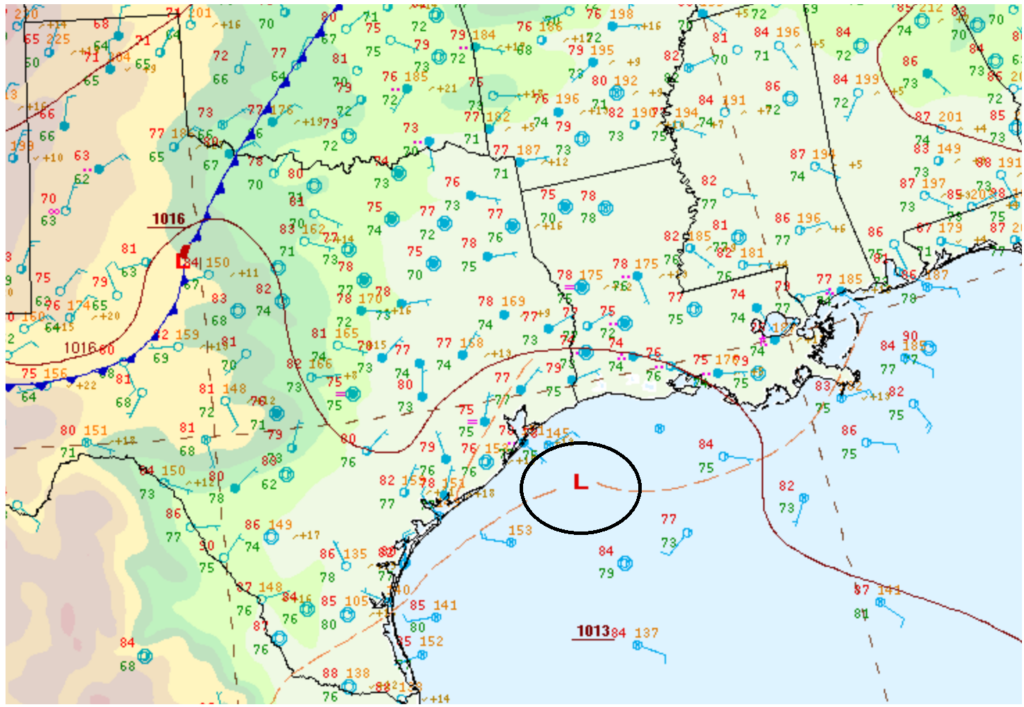

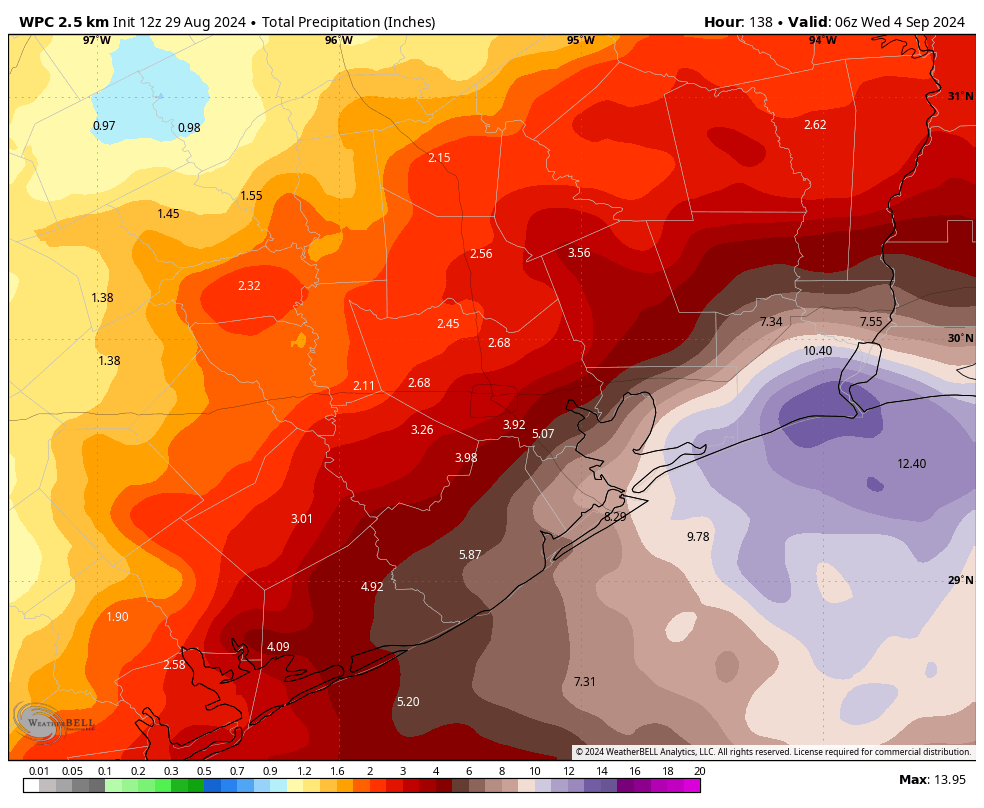

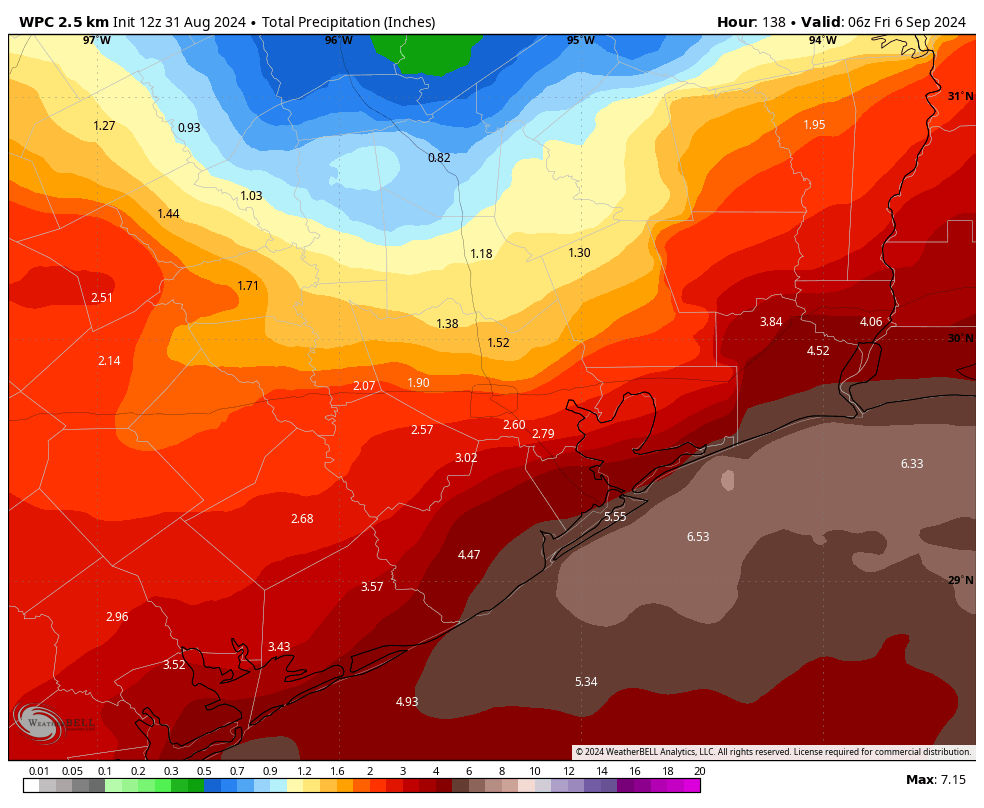

The rains into next week will be driven by an upper-level low pressure system lingering off the Texas coast. As we discussed on Friday, there is a small possibility this system develops tropical characteristics with a surface center of low pressure over the Labor Day weekend, but most likely its main impact will be as a rainmaker for coastal areas.

As often happens with these systems, the heavy rainfall is clustered mostly offshore. But areas such as Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula will be well within the threat area, and may pick up 5 or even 10 inches of rainfall through the middle of next week. It won’t rain all of the time, but coastal counties should expect a pretty decent soaking through about next Wednesday.

As for areas further inland, including most of the Houston metro area, showers will be hit or miss this weekend. Rain chances will depend on how far you live from the coast, but over the Labor Day weekend you can at least expect a healthy chance of a passing shower or thunderstorm each day. One benefit of the cloudy skies this weekend is cooler temperatures, particularly for the end of August and into early September. Highs, for the most part, will be in the upper 80s to about 90 degrees each day—and even cooler closer to the coast. Often, we’re 10 degrees hotter at this time of year.

Tropics

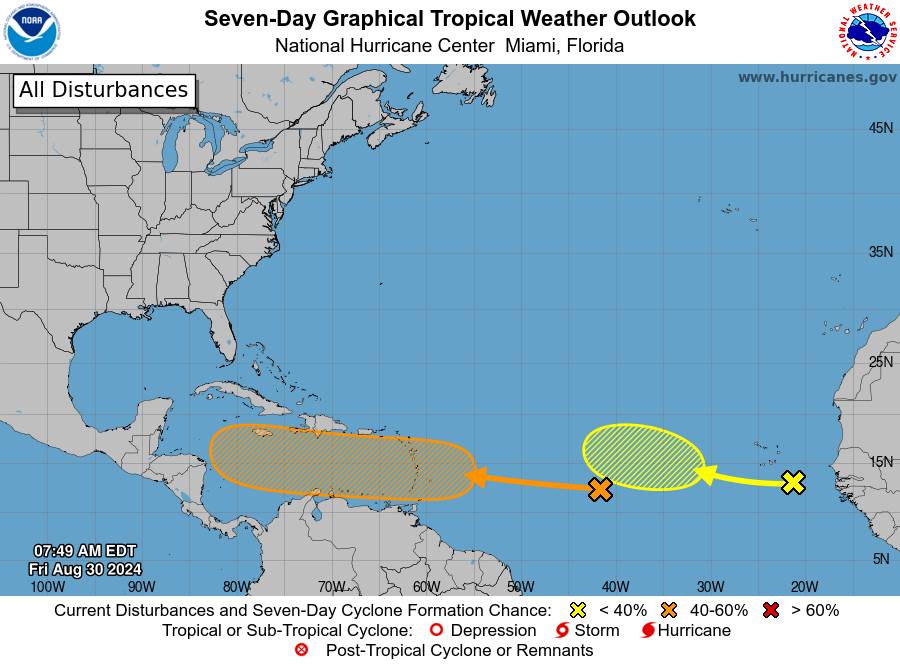

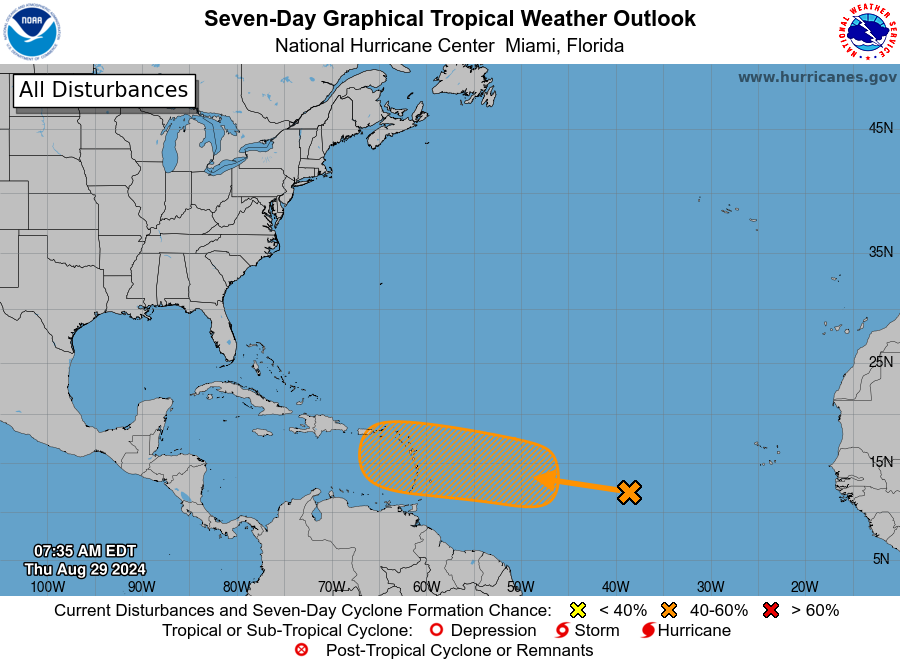

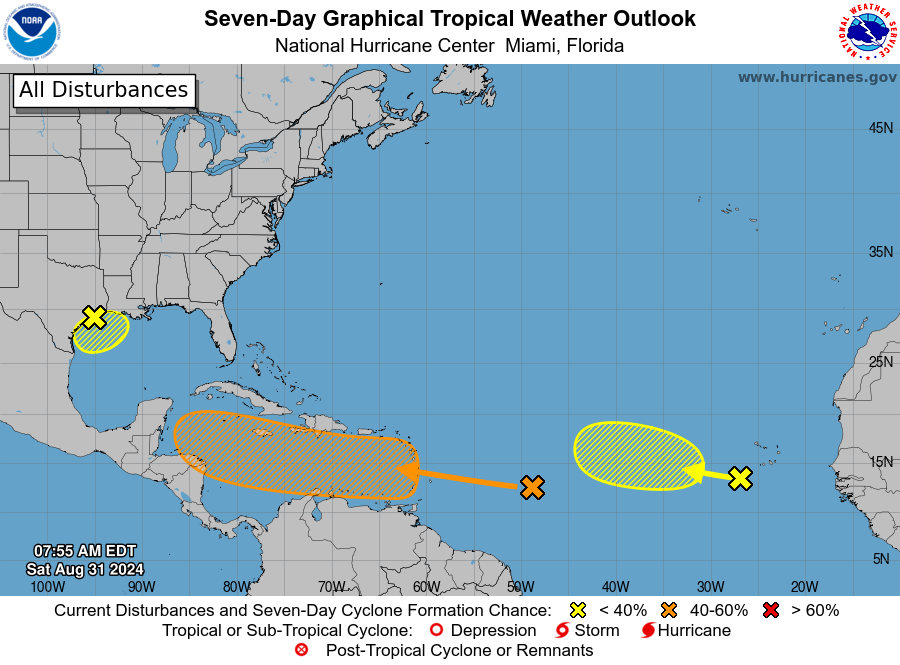

We’re starting to see activity pick up in the tropics. If you want a full rundown, please check The Eyewall later this morning, where Matt will have a comprehensive update on everything we know before noon today. In addition to the aforementioned system in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, we’re also closely monitoring a tropical wave in the Central Atlantic. It will move into the Caribbean Sea early next week.

There it will find blazing hot seas, but at this time most of our modeling guidance is not too aggressive about developing it into a tropical storm or hurricane early next week. However, toward the end of next week this wave/tropical system will be nearing the western edge of the Caribbean Sea. After that point it could move into the Gulf of Mexico. We’re talking about a period 7 to 10 days from now, so uncertainty is very high. There’s not a whole lot we can say about what happens at that point, so we’ll continue to watch it.

Have a great Labor Day Weekend, everyone. We’ll be back with another post on Sunday morning to assess things.