The summer solstice arrived late on Sunday night, at 10:32 pm CT. The solstice, of course, is the longest day and the shortest night in the Northern Hemisphere, and results from the 23.4-degree tilt in the Earth’s axis and the planet’s rotation around the Sun. The solstice begins a three-month period known as “astronomical summer.”

In Houston, of course, it generally feels summer-like from June through September. Although our days will now slowly begin to grow shorter, due to our proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and a lag in oceanic warming (and cooling), most of our summer heat comes after the longest day of the year.

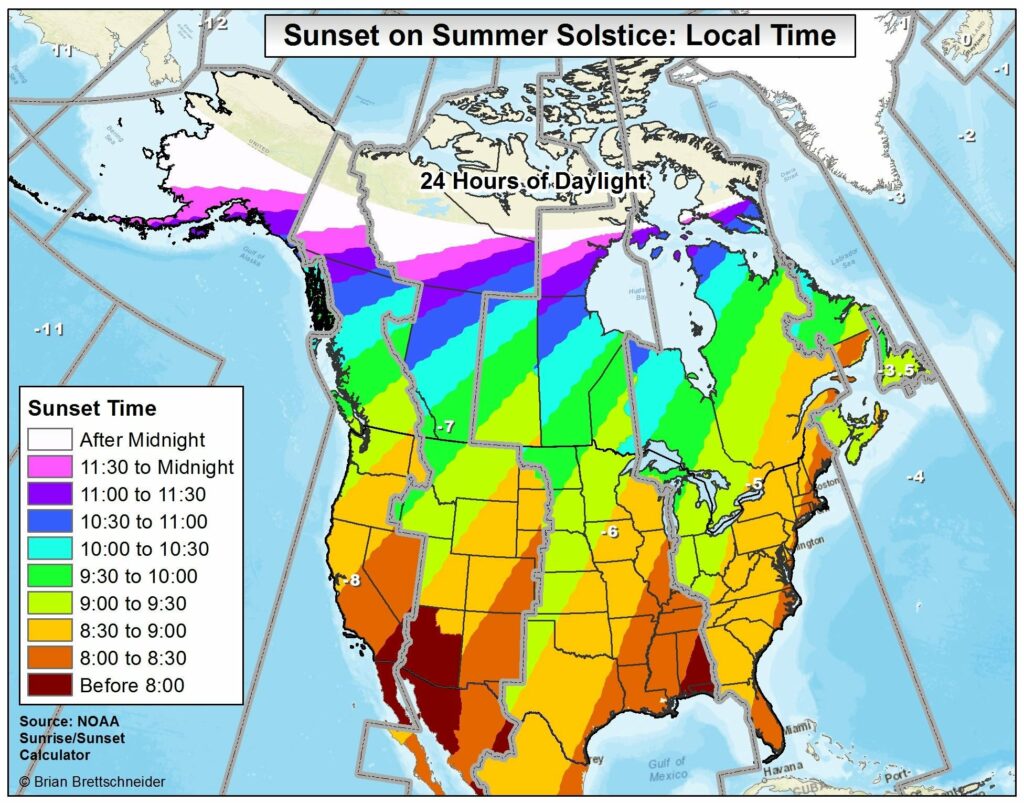

The following map, shared by Brian Brettschneider on Twitter, shows the the time of the sunset across the United States and Canada on the summer solstice. This is affected both by the solstice as well as time zones that humans have created around the Earth. The area that sees 24 hours of daylight on the solstice, of course, lies above the Arctic Circle.

As for our weather this week, we will experience a couple of more wet and slightly cooler days before high temperatures return into the mid-90s for the second half of this week.

Monday and Tuesday

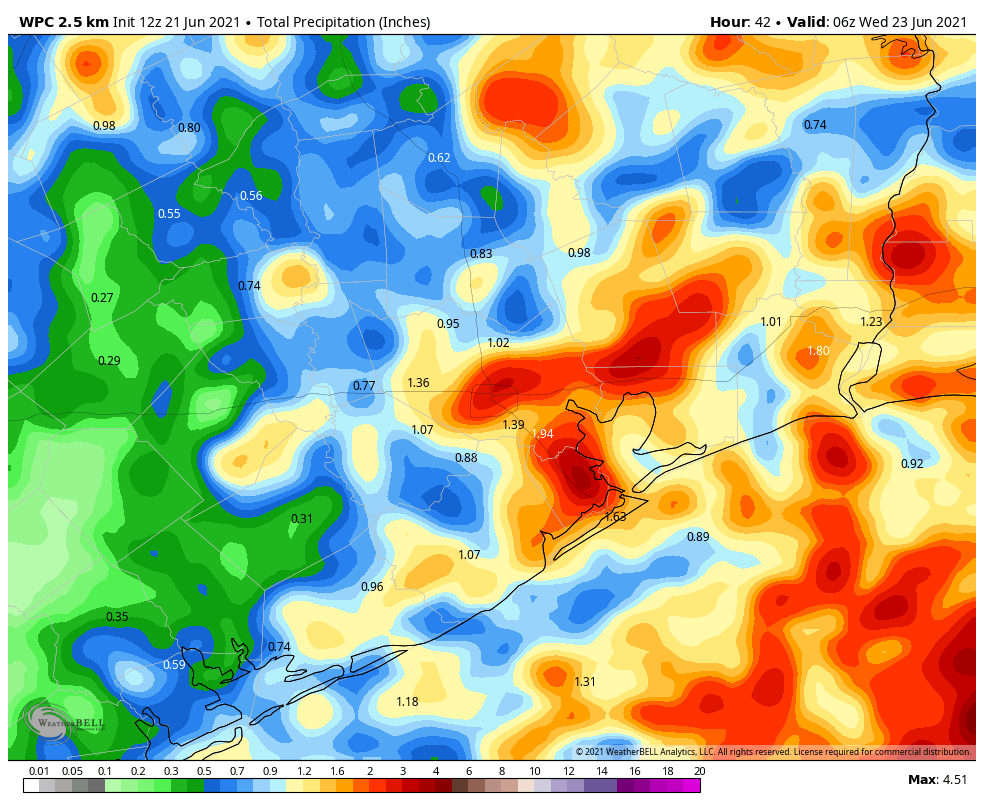

Our weather over the next couple of days will be driven by a cool front—and we’re using the meteorological definition of a front, because it won’t have too much effect on how things feel out there. This front will act to increase the likelihood of rainfall on Monday, Monday night, and Tuesday morning. I don’t think we’re going to see widespread, heavy rainfall, but some of the showers that develop will be capable of fairly intense rainfall rates. I think much of Houston will see 0.5 to 1.5 inches of rain, with a few bullseyes of 3 or more inches possible. Our best rain chances will likely come during the overnight hours.

In terms of temperatures, most of us will see highs around 90 degrees for the next two days due to the combination of cloud cover and the front. Will you feel it? If you live inland of Interstate 69/Highway 59, and you go outside on Tuesday evening or Wednesday morning, it may feel slightly drier outside.

Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday

For the second half of the week we should see mostly sunny skies as high pressure begins to build over the area. Highs will likely rebound into the mid-90s and we’ll be right back into full-on summer days in Houston, with overnight lows of around 80 degrees.

Saturday and Sunday

The weekend forecast is a little bit less certain, as yet another front is likely to approach the region. However, this one very likely will stall out before reaching the Houston metro area. Nonetheless it may introduce some clouds and rain chances for the weekend. It does look like Saturday will be mostly sunny, and while there may be some scattered showers, the chances for wider rainfall likely will not come until Sunday. But all of these details will need to be hashed out in future forecasts.

Loved the first map. It explains why as kids we were able to play Wiffle Ball until almost 10 PM in mid-late June. North plus western part of Eastern time zone

It also looks like Indiana finally decided to adopt Daylight Savings time. ‘Bout time. Pun intended.

It’s been about 15 years since they made that change. It used to be such a pain having to remember when Indiana was the same as Central time and when it was the same as Eastern time.

I used to like not having to reset everything twice a year when I lived in Indiana. It was in Eastern standard year round.

When I was in college (in Terre Haute) , Evansville was on central time and went on DST two weeks late. So for two weeks, Evansville was TWO hours behind Cincinnati. Strange.

Warming stripes for Houston 1892-2021 from climate central

https://images.climatecentral.org/2021WarmingStripes/2021WarmingStripes_houston_en_title_lg.jpg?rtc_tracking_dmid=0895341396030658356&rtc_tracking_is_link=1

Why do some weather systems include lightening while other, seemingly like, systems don’t? What determines c to c vs c to g?

A little late to the game here but:

The biggest determinate for lightening is cloud height and the churning of dust in the cloud column. Friction between the colliding dust grains create the electrical charge). Lower altitude (cloud tops) tropical type storms produce a lot of rain but little lightening. Mesoscale storms (very high cloud tops with lots of updraft) can produce a lot of lightening and a lot of rain. The key is there needs to be dry air near the cloud tops for the lightening to form. Think rubbing your feet on the carpet to produce static electricity. Doesn’t work so well when the carpet is damp.

For your second question lightening seeks out the shortest path to electrical ground. Usually that’s the ground itself but occasionally a nearby cloud will have enough of a negative charge (or positive in some cases) to attract the lightening, diverting it from hitting the ground.

Thanks for the very interesting sunset map.

would it be possible to darken or better outline the county lines on the maps? Very hard to see the counties to determine what part of the information applies to me.

I like that sunset map, thanks for sharing it!