Here’s the best of Saturday’s Facebook Q&A with Eric. This late-morning session drew more than 400 questions, and Eric was able to get to 60 of them. You can find the best answers from Friday’s initial Q&A here. Stay warm and safe, everyone!

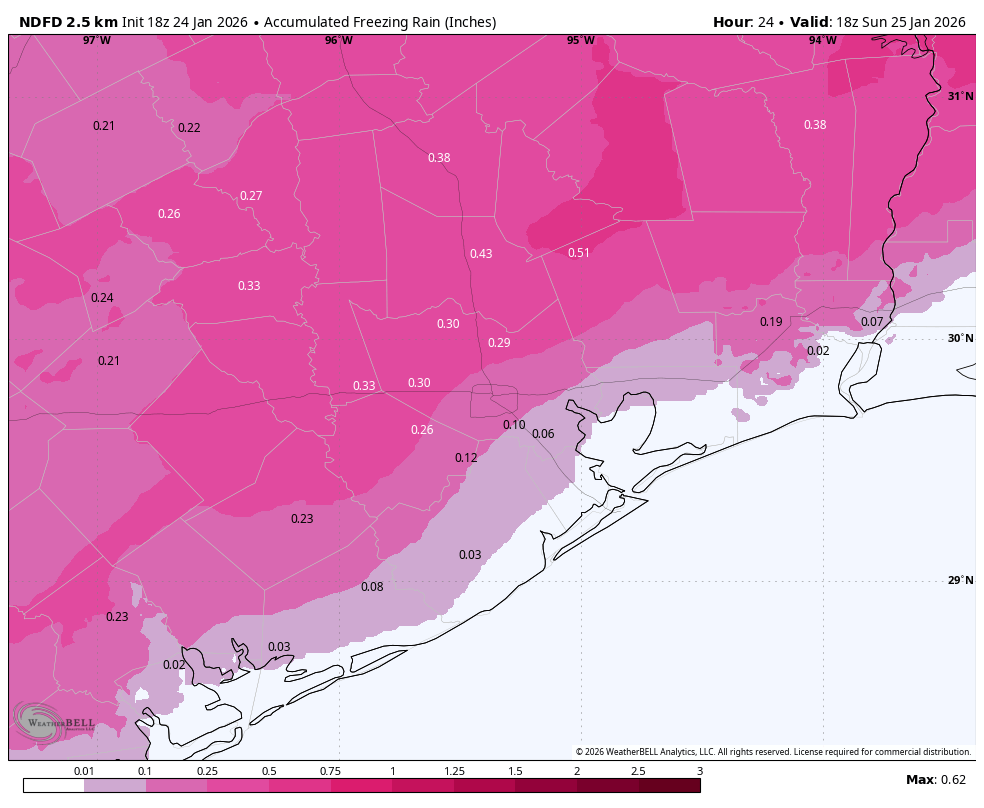

Q. What has changed from your last Q&A?

A. We are a little more confident in freezing rain reaching into the Houston metro area than on Thursday. That is, we now think it’s likely to reach at least the Highway 59/Interstate 69 corridor. How much further south than this? I’m not sure.

Q. Will the rain fall as rain or ice tonight?

A. It depends a lot on where you live. Basically, at this point, if you live along and inland of Highway 59 I would bet on a transition to freezing rain at some point after midnight. South of that, and closer to the coast, it’s still too close to call.

Q. Any more clarity on high temps Sunday?

A. At this point I think areas along and inland of Highway 59 will remain at or below freezing. Areas closer to the coast probably will get to about 35 degrees for a few hours.

Q. Will it be safe to drive Sunday evening in the cypress area ??

A. You’re going to have to make a game-time decision on that. You should know by late Sunday morning what conditions are going to be for the rest of the day. At this point I’d definitely be planning for the possibility of hazardous roads in the area.

Q. How well are the models performing so far, in terms of predicting the influx of colder air?

A. Pretty good so far. They were good on the timing and extent of the rain showers, and so far we’re seeing the temperatures we expect to see on Saturday.

Q. Is there going to be enough ice to lose electricity?

A. Hopefully not! But I’m concerned about ice accumulations in areas north and west of Houston on Sunday morning.

Q. What are the odds that the roads will be mostly closed on Monday around noon?

A. For areas along and inland of Highway 59, I’m going to go with 50 percent or greater, and for areas closer to the coast less than 50 percent.

Q. Why is the forecast so different on different news stations? There does not seem to be a lot of consistency.

A. It’s because the line of freezing rain/cold rain is likely to fall somewhere in the greater Houston area on Sunday. We cannot say precisely where, however, and so depending on the suite of models you’re looking at, the answer is going to vary. Also keep in mind that it’s difficult to message for such a large metro area where you know for sure people in places like Conroe and Hempstead are going to be dealing with ice, and others in Galveston are not. So it’s a big communication challenge in addition to the forecasting difficulty.

Q. For those of us who are on the border of two LARGE counties (Galveston & Harris), how do we know which weather alerts to pay attention to? It’s difficult to discern when one county is alarmed at something and another is not.

A. It’s a good question. I also live right on the border of Galveston and Harris County. This is why we include forecast maps so you can see temperatures close to where you live. Also be mindful that there’s a huge difference, often, between weather in NW and SE Harris County. Obviously you’ll want to pay attention to what is said about SE Harris County.

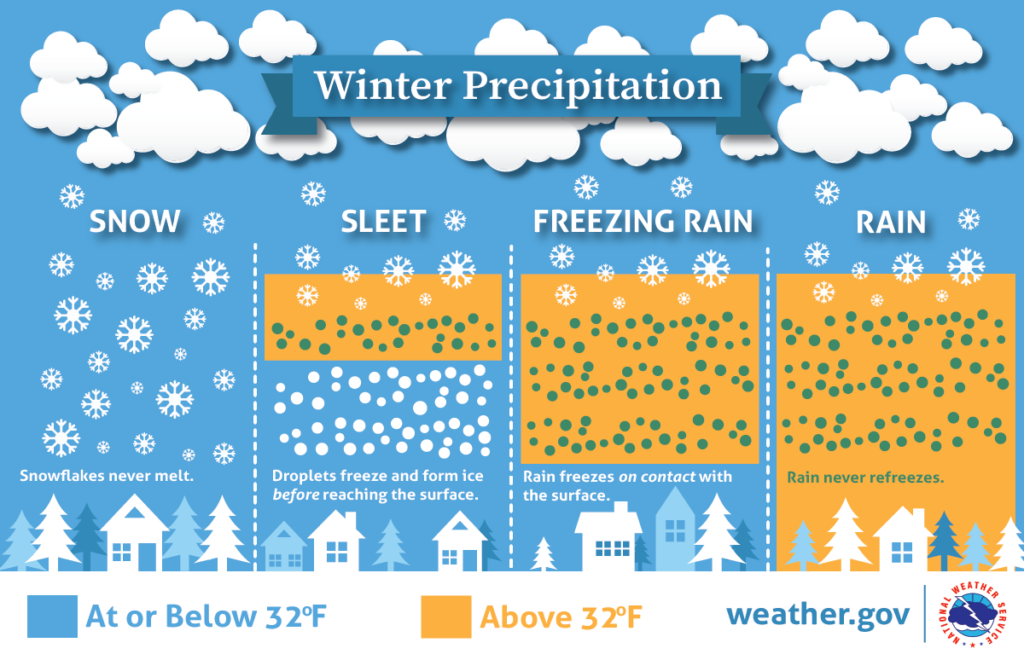

Q. Forecasters are saying “freezing rain”. But what’s the difference between freezing rain and snow or sleet?

A. This chart is never not helpful!

Q. Are we okay to be on the roads through this evening? Is there a time you suggest we need to be off? We have community cats that are outdoor but have heated cat houses on the porch should we bring them inside? Pasadena/Pearland areas

A. Yes, roads will be safe until at least 9 pm CT, and probably a few hours later. Animals should not be left outside, in non-heated structures, on Sunday and Monday nights.

Q. I’m doing a one-woman show at MATCH (Midtown MATCH – Midtown Arts & Theater Center Houston) tonight that runs from 7:30 to 8:45. Most of my attendees will be from central Houston (inside loopers). Are they going to be okay getting home after the show, which BY THE WAY, you and Matt play a large role in for your consistent and reliable Houston weather reporting. Literally, the part of the show where I call you out in an homage to your service to us, got not only one of the biggest laughs (of hearty recognition), but also 100% of head shaking nods of “don’t we know it!” I wish you guys could come see it!

A. Good luck with the show. I think people should be fine getting anywhere in metro Houston up until about 9 pm, and probably several hours later for most locations. I would say it’s fine to go on with the show, but at the same time I would understand if someone from Conroe decided not to attend.

Q. What’s a question you wish someone would ask but they never have?

A. Eric, how is it that you have stopped aging?

Q. Thanks for keeping us informed. Do you see this storm similar to Uri (2021), what is the same and what is different?

A. The storm will both be of much shorter duration (two days instead of four, roughly) and intensity (air temperatures likely 5-10 degrees warmer at the coldest) than the hard freeze in February 2021. In addition we don’t expect the widespread power disruptions experienced during Uri which made things a lot worse for everyone.

Q. Healthcare worker here that needs to get between League City and Galveston…Do you anticipate ice on the Causeway at any point?

A. It’s a good question, Amanda. At this time most of the model data does not show freezing rain making it that far south on Sunday. I’m also hopeful that the combination of road treatment and above-freezing temperatures on Sunday afternoon will dry the Causeway out.

Q. What are the odds of ice on Tx Med Center area roads pre-dawn Tuesday?

A. Very low, probably less than 10 percent.

Q. Can we have snow instead?

A. Not this weekend. There’s a non-zero chance of some flurries about a week from now, however.

Q. My daughter works till 11 pm tonight in the Atascocita area. I’ve been watching all the news channels on the timing of the freezing rain/freeze line & one said it would be around 9pm for our area. Everyone else is saying after midnight so now I’m stressed. I read your post earlier but has anything changed as far as timing & it being earlier? Thank you.

A. There are no absolutes right now, but I would feel comfortable with my daughter on the roads at 11 pm tonight. She should come straight home afterward, however.

Q. I know this is a long shot but traveling from Hobby area to fly out of IAH on Monday @5am. Flight is at 8am.

A. It’s probably 50-50 at best. I’d switch it if you can.

Q. I’m originally from Michigan, living in Splendora, working in Cleveland. I’ve seen so many different forecasts. What do you think my areas will actually get? Snow? Ice? Will it be safe to drive to work at 5am Monday morning?

A. I’m from Michigan as well. How are you enjoying this October-like weather? (kidding)? I think you’re going to get some freezing rain and icy roads on Sunday. I would put the odds at roads early Monday morning there being “mostly passable” at less than 50 percent.

Q. Thoughts on ice accumulation on power lines in the Spring/ Klein area? I heard Ercot “ramped up” their facilities to hold power? Hearsay?

A. ERCOT is responsible for power generation. I know they are preparing for the storm. But as for power lines, those are (largely) maintained by CenterPoint in the greater Houston area. I know they are making preparations as well. But if ice accumulations over perform expectations there will be issues with snapped power lines.

Q. Will the ponds freeze enough to play pond hockey?

A. Potentially by Monday morning! I’d exercise ice safety, however, by determining its thickness before venturing too far out.

Q. At what temp should we consider turning off water to house? And thank you to infinity.

A. Interior pipes are generally safe until exterior temperatures fall to 20 to 22 degrees, although that really depends on the particular insulation of your home.