Let’s talk about minimum temperatures. The city of Houston has now recorded five consecutive mornings of 80-degree plus temperatures. This average of 81.6 degrees trails only a five-day period in 2011 (81.8 degrees) for the warmest stretch of minimum temperatures in about 120 years of records for the city of Houston.

Looking across the entire globe, climate scientists have been noticing this trend for some time—that as the planet warms nighttime temperatures appear to be warming faster than daytime temperatures. In Chapter 2 of the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the authors write, “Confidence of accelerated increases in minimum temperature extremes compared to maximum temperature extremes is high due to the more consistent patterns of warming in minimum temperature extremes globally.”

Why is this happening?

Now there’s no question that development around northern Houston has played some role in warmer temperatures around the National Weather Service’s official station at Bush Intercontinental Airport. This is the so-called Urban Heat Island effect. However it would be wrong to attribute the nighttime warming to urbanization alone, as the global trends are pretty clear. Warmer nights locally are consistent with a warmer world.

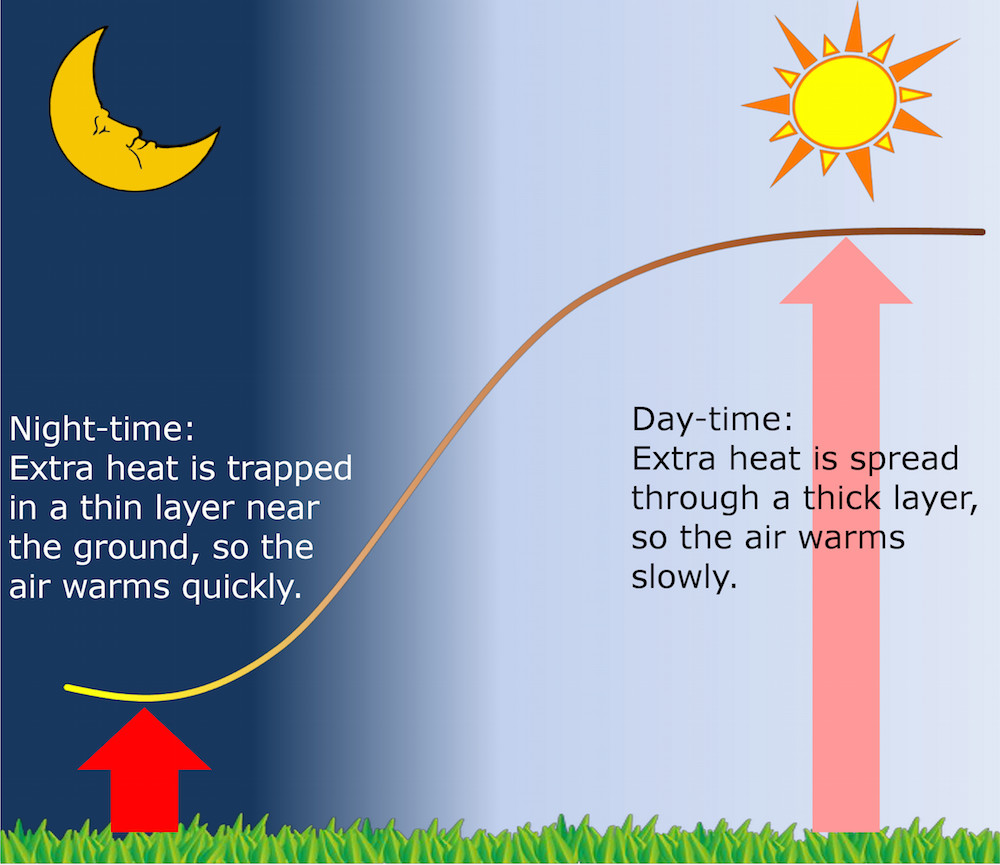

That raises another question: Why would nighttime temperatures be increasing faster than daytime highs? One plausible explanation has to do with the thickness of the “boundary layer,” which is the layer of air right at the surface of the Earth which is distinct from the rest of the atmosphere. This boundary layer is quite thin at night, and thickens during the day. One recent study of the boundary layer above Houston found that, during the summer months of June, July and August, the boundary layer was about 200 meters thick at night, and nearly 2,000 meters thick during the late afternoon hours.

As we know from the basic greenhouse theory, increased amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases reduce the amount of heat that is radiated back into space from this surface layer. When the boundary layer is thinner at night, with a much thinner volume, this warming effect is more concentrated. During the day, when the boundary layer is thicker, the heat is dissipated over a larger area, further above the surface of the Earth.

The process is almost certainly more complex than this, but the bottom line is that we can expect to see more 80-degree nights in Houston’s future than we have in the past.

So, what makes the boundary layer distinct from the rest of the atmosphere? And why does it thin at night?

Hi Richard. There’s some good background information on the boundary layer here: http://www.theweatherprediction.com/basic/pbl/

The simplest way to think of it is the layer of air directly influenced by contact with the surface of the Earth, and the friction that entails with various types of terrain.

Eric, help me better understand this. Your illustration says “Extra heat is trapped in a thin layer near the ground, so the air warms quickly.” Can you elaborate on this? Specifically, what do you mean by “the air warms quickly”? Unless warm air advection is occurring (not at all typical during the summer months), then the boundary layer cools at night due to radiational cooling. It almost sounds as if you are implying that the CO2 concentration is vastly different in the boundary layer than it is in the free atmosphere immediately above it. I don’t think this is true. I think a far more plausible explanation is that the primary culprit is in fact increased development. It’s far easier for the heat stored in concrete and steel to raise nighttime temperatures than daytime temps. Look at it this way: add enough energy to your oven to raise the temperature to 350 degrees for two hours, then turn it off and measure the temperature two hours later. Repeat the exercise, this time with 4 bricks in the oven. I’m pretty sure you’d end up with a higher temperature at the conclusion of the second experiment. I recognize that increasing nighttime temperatures are being seen globally, but I would argue that that increased development has also occurred worldwide. Start by reviewing available nighttime temperature data from the local area. First, considering historical data, I’d be shocked if the nighttime temperature differential between Hobby and IAH hasn’t shrunk considerably over the last few decades. This would be expected if the primary cause is development, because 30 years ago Hobby was already in an urban environment, while IAH was still very rural. Second, just look at the current/recent low temps reported from “unofficial” mesonet stations located a similar distance from the coast as IAH in northern and northwestern Harris County. I’m located in Cypress, and while it’s true that we’ve experienced some warm nights of late – even some greater than 80 degrees – we did not have a similar string of nights over 80 degrees. I recognize that PWS data is not as reliable as the official readings, but if anything, data from PWS’s is biased towards the high side.

If the boundary layer does play a role in this, I think it is more likely due to the increased development causing an increase in turbulence, which in turn increases the thickness of the nighttime boundary layer relative to earlier times. Isn’t radiational cooling most efficient when there is little to no atmospheric mixing (i.e. a very thin boundary layer)?

I might be missing something, so I’d appreciate a more in-depth explanation of your post. Admittedly, we’re on different sides of the aisle when it comes to the primary drivers behind the recent warming, but I’m open minded and truly want to understand all sides of the argument.