In brief: In today’s post we discuss the rumors about a “snow bomb” hitting Houston around Valentine’s Day (you will be shocked to learn the rumors are not true). We also discuss our moderating temperatures this week, and what looks to be a splendid weekend ahead.

Gulf coast “snow bomb”

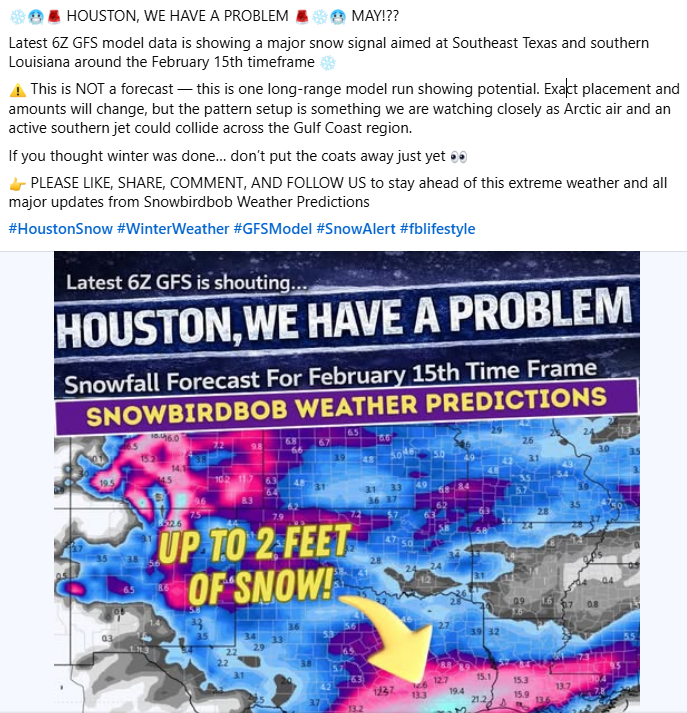

Matt and I began to receive some messages on Saturday morning about the potential for the greater Houston region to receive another Arctic blast around Valentine’s Day. The questions kept coming on Sunday, along the lines of, “rumors are circulating …” about the threat of a major snowfall in the region. We were scratching our heads because there were no valid indications of such an occurrence.

Nevertheless we did a little digging. It was pretty clear from the outset what precipitated the concerns. A single run of the GFS model, the 06z output on Saturday morning (publicly available about 5 am CT, usually) showed a ridiculous amount of snowfall across the Houston area, like two feet. It would set records. Such an event would be historic. But of course there was no real reason to believe a model output that was forecasting an event two weeks away. That is the “silly season” range of model output, and the US-based GFS model is notoriously bad with these kinds of things. And as one might expect, by the very next run, this snowfall was completely gone. Poof!

This, alone, would not have been enough to spark questions. But then my wife stumbled across this post on Facebook later on Saturday morning. Note that it contains a double dose of dumb because the “author” uses the “Houston, we have a problem” cliche.

This nonsense, therefore, came from a deadly duo in today’s day and age when it comes to weather information. First you need a single model run showing a long-range forecast more than 10 days out. Then you need a social mediarologist to spread the hype. It’s a pretty unstoppable combination. But as a consumer there are a couple of things you can do to combat this. First of all, check to see how far out the forecast is. If it’s 10 days or greater, be super wary. If it’s forecasting an extreme event, be super super wary. And if the post uses the #fblifestyle hashtag, you can have a good laugh because this is not a serious person.

Really, all you need to do is check Space City Weather. If there is a credible chance of a major winter storm in Houston, we’ll be talking about the possibility. We promise.

Monday

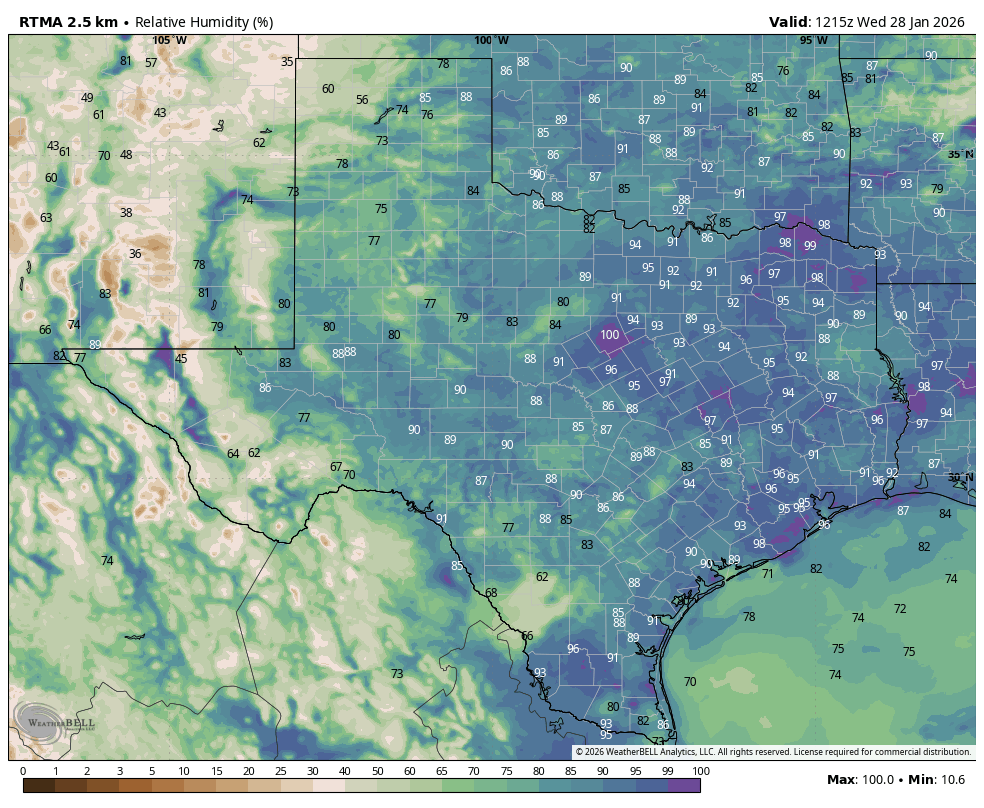

Temperatures this morning have bottomed out at about 40 degrees, and we are already seeing a southerly flow that will warm us up nicely this afternoon. Expect highs of about 70 degrees. We also will see increasing cloud cover as atmospheric moisture levels ramp up. As a result low temperatures tonight will only briefly drop below 60 degrees.

Tuesday

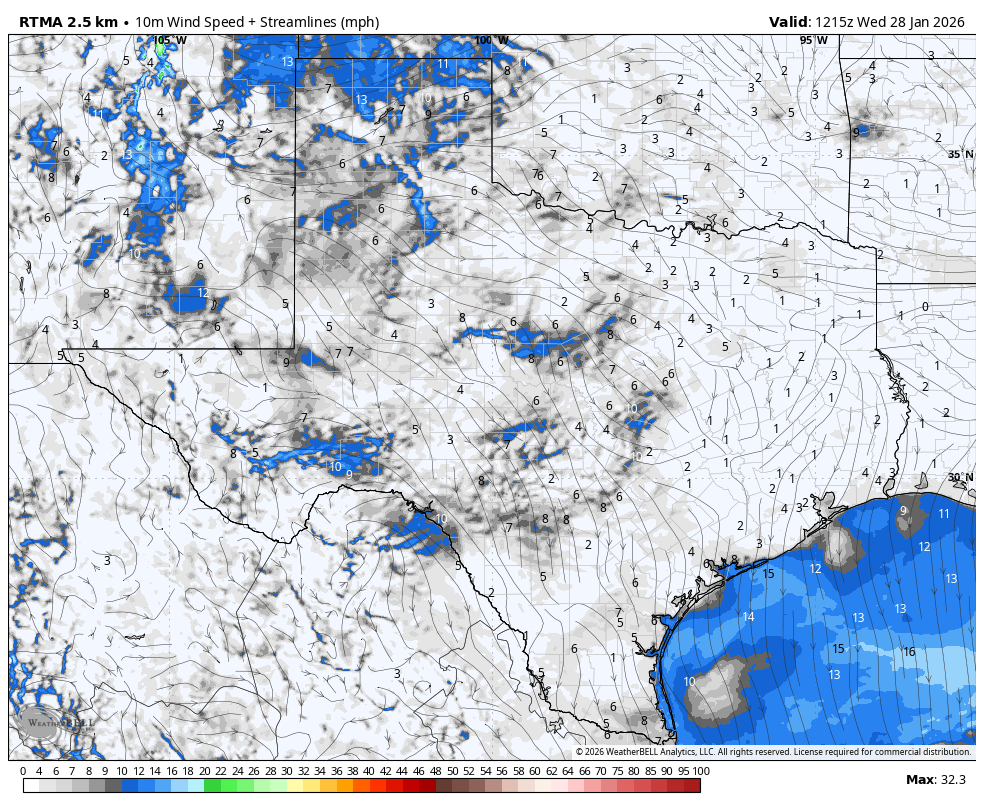

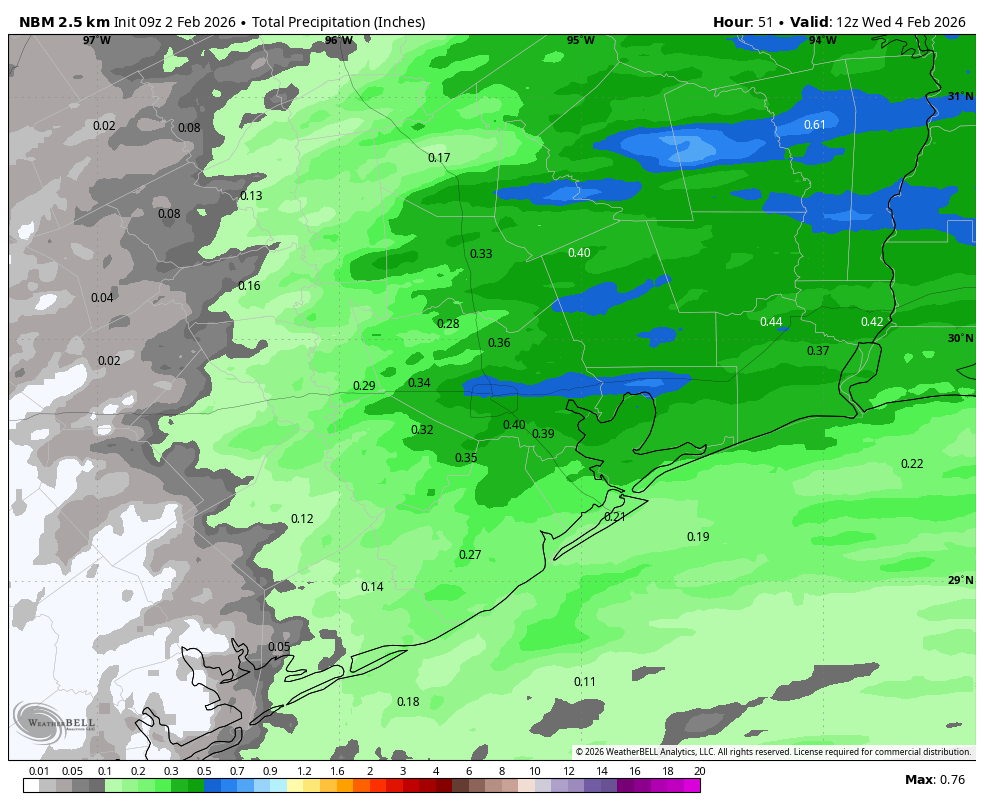

This will be a mostly cloudy and warm day, with high temperatures generally in the low 70s along with southerly winds. We also will see a chance of light showers during the daytime. By late afternoon, and during the evening hours, a front will approach the area and we may see a line of broken showers and a few thunderstorms. These will persist until around midnight or perhaps a bit later down by the coast. Rains will probably be hit or miss, with some locations picking up a trace of rain and other areas one-half inch or more. Temperatures will start falling after midnight.

Wednesday and Thursday

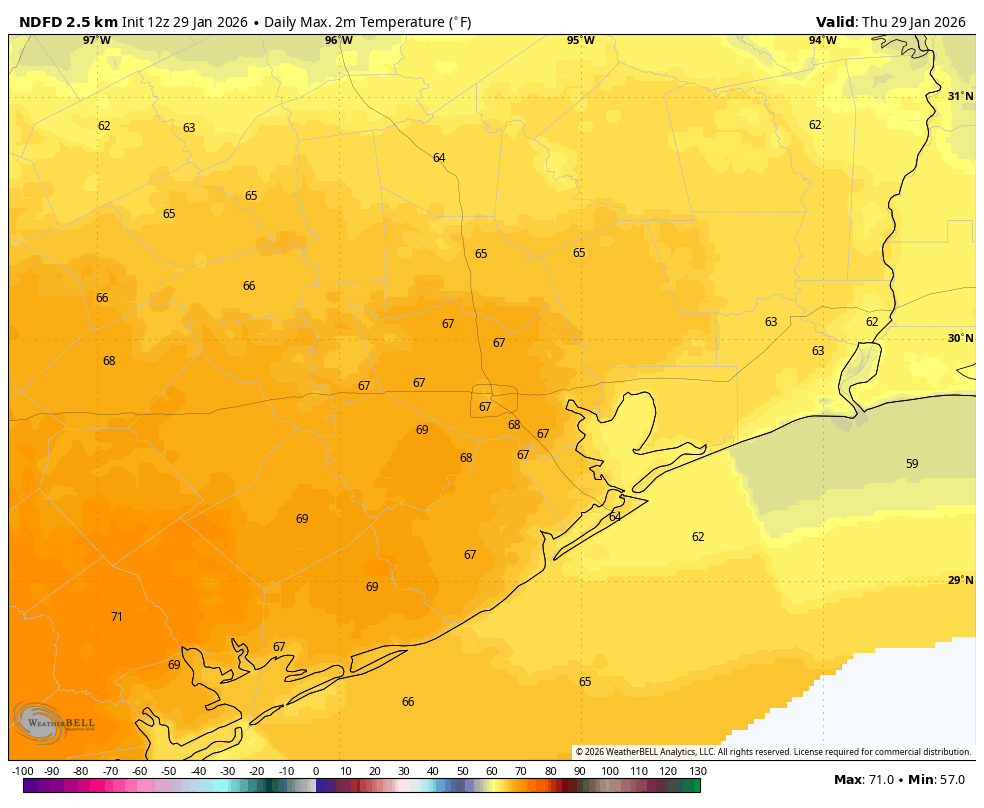

These will be fine, sunny days with highs in the low- to mid-60s and overnight lows in the low- to mid-40s. Wednesday may be a bit breezy.

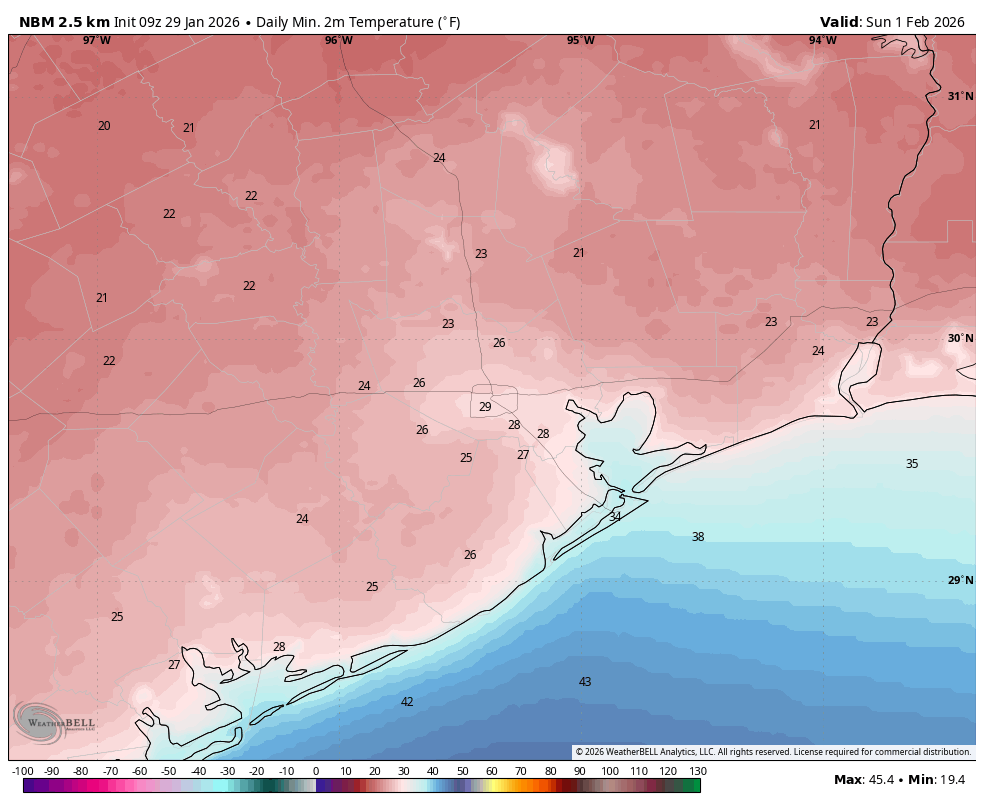

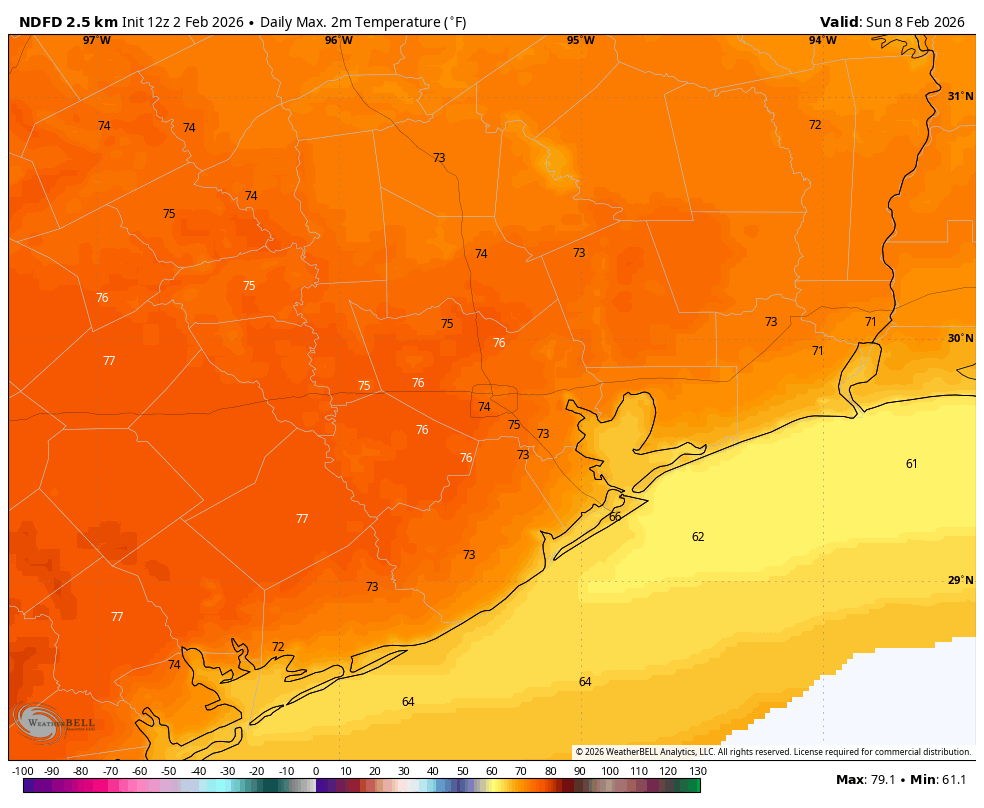

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday

If you have outdoor plans scheduled for this weekend, you’re in lucky. We should see mostly sunny skies on Friday and Saturday, with a few clouds returning by Sunday. Highs will be in the low- to mid-70s through the weekend, with overnight lows in the 40s and 50s. It looks positively gorgeous for any outdoor activities.

Next week

The first half of next week looks to be on the warm-ish side, with highs in the mid-70s perhaps and lows in the upper 50s to about 60 degrees. Some kind of front may push through by around Thursday or so, to cool things off a bit, and bring a chance of rain. The front may drop overnight lows into the 40s, or it may not have that much oomph.

So what about the snow chances for Valentine’s Day? Well, perhaps if you’re traveling to Boston for the weekend.