In brief: Mainly quiet, pollen-ridden weather through tomorrow in Houston, followed up by more scattered-type showers and storms Sunday through Tuesday. A cold front that’s more like a humidity front continues to look plausible around midweek next week. The tropics remain quiet for us.

Today & Saturday

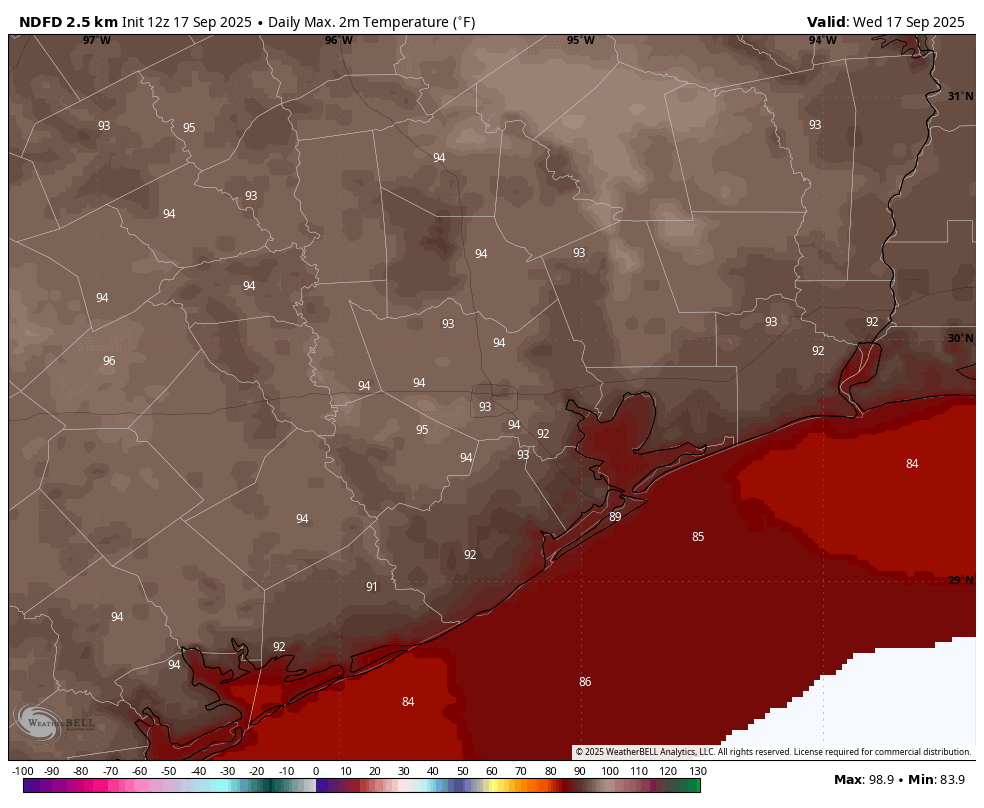

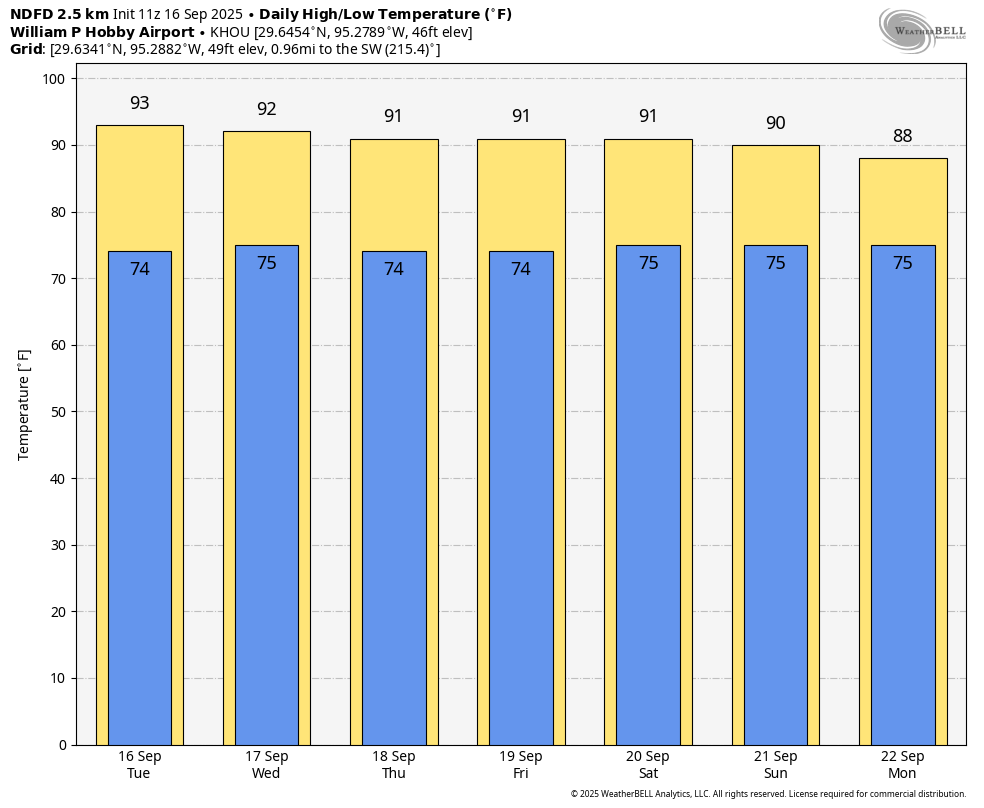

Our late summer slog continues with hot days, warmer than normal nights, and generally high humidity (though at times it feels decent outside at least). Isolated showers are possible today, and we may see isolated to scattered showers or a thunderstorm tomorrow. Overall, nothing too bad. Temperatures will be in the low-90s for highs.

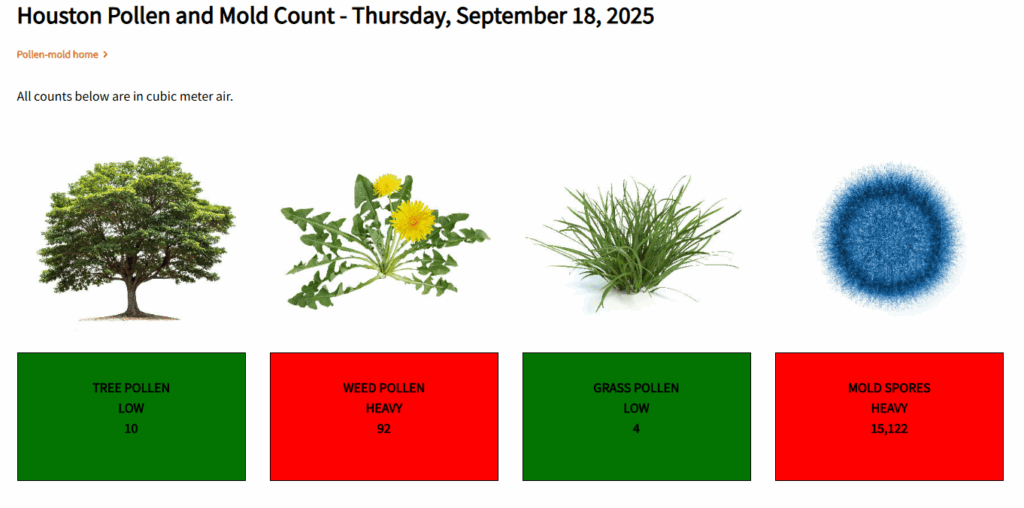

An ozone action day is in effect again today. For most people this will not be an issue, but for those of you in sensitive groups, try to avoid being outside except early and late in the day. Also, for those of you (like me) that have had the sniffles lately, there’s a good chance that ragweed is the culprit.

The typical autumn nemesis.

Sunday through Tuesday

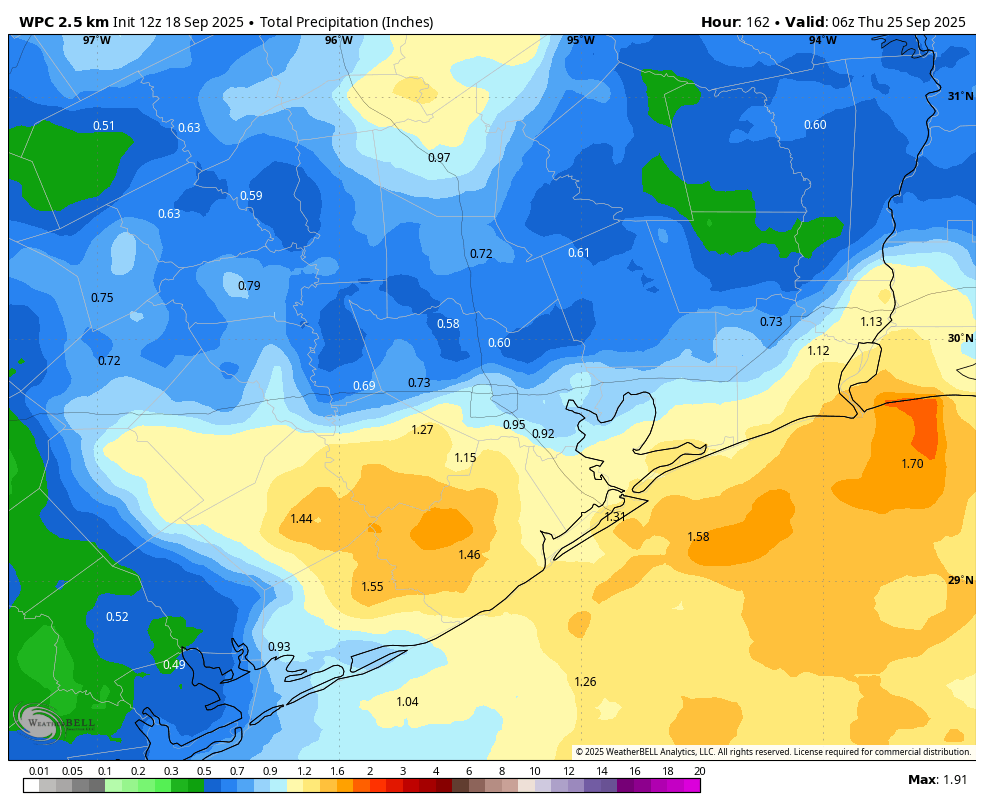

Scattered showers and thunderstorms should be the name of the game beginning Sunday. While this will still be a patchwork type rain setup, a few more folks should begin to participate each afternoon. Expect continued highs in the low-90s but perhaps some slightly cooler afternoons at times due to the showers. Lows will remain mostly in the 70s.

Wednesday front!?

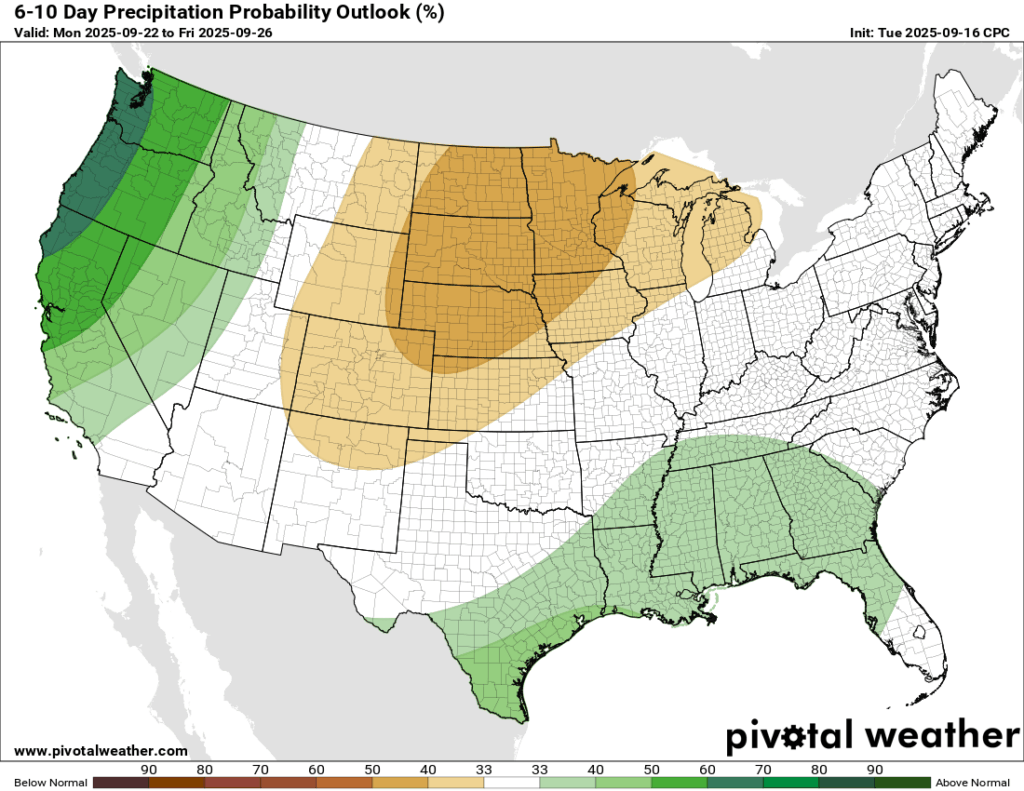

Eric has mentioned the potential of a cool front next week, nothing spectacular but a potential notable change for a couple days. That remains very much on the table today. The timing is a bit suspect, but sometime in the Wednesday or Thursday timeframe, it appears that a weak front will drop south into the area, bringing the potential for scattered to numerous thunderstorms for a short time. Behind the front, we’d turn a little cooler and a lot less humid to close out the week.

You can see the European model forecast of dewpoint for midweek, showing a distinct drop in dewpoint levels on Wednesday evening into Thursday and Friday. This is more of a humidity front than a cold front, though the lower humidity should translate into a chance at widespread lows in the 60s by Friday morning perhaps. With the Autumnal Equinox on Monday afternoon, we do see signs of fall sprinkling the forecast.

Tropics

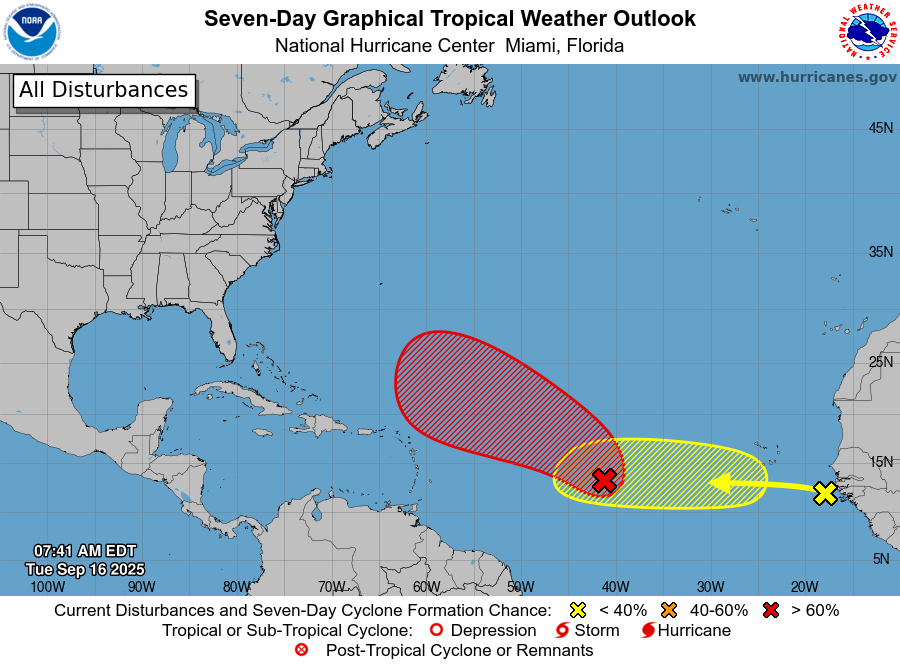

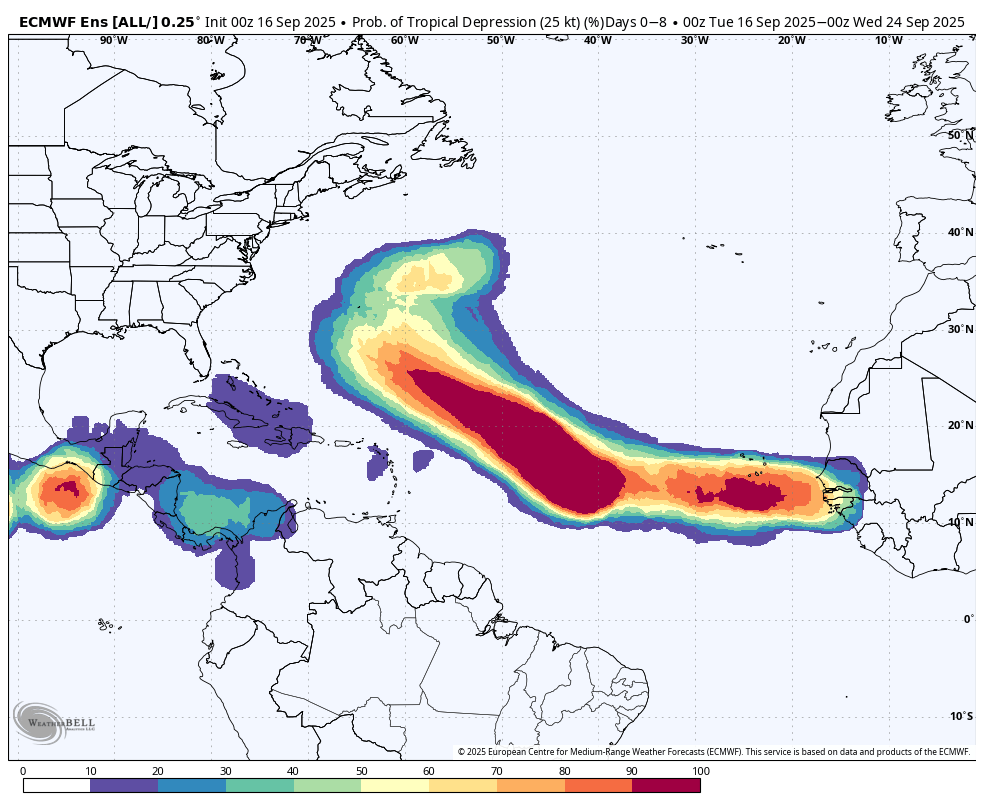

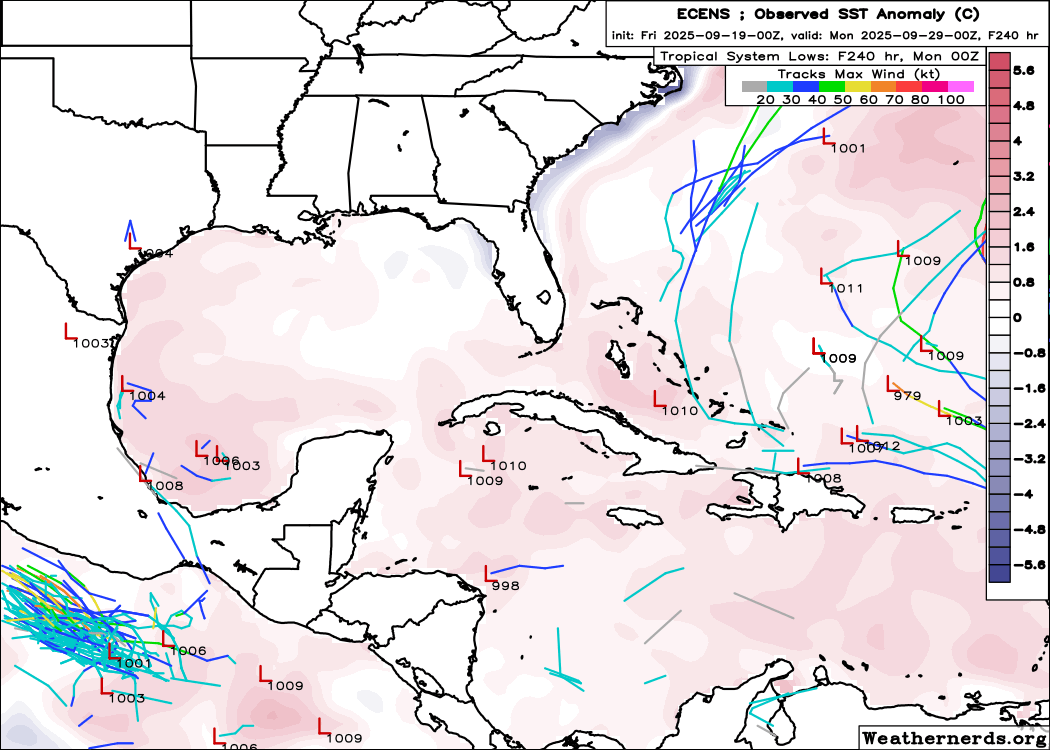

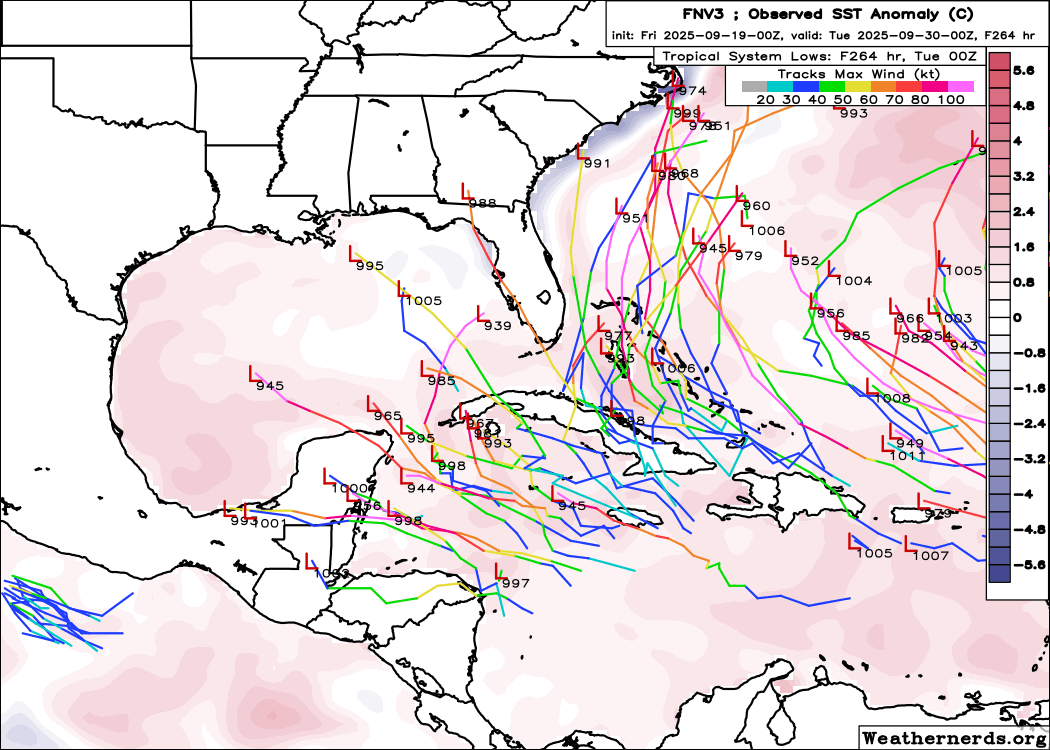

Gabrielle is slowly building in the Atlantic, but that’s where it will stay. Another wave behind Gabrielle has some development risk, but that also looks to stay in the Atlantic. Is there anything to focus on for Houston? Nothing specific. There’s a general trend, particularly with AI models to try to spin something up in the northwest Caribbean in about 10 days, but that’s not supported much in the traditional physics-based models.

So this will be a good test for AI modeling: Are they capable of “seeing” a tropical genesis risk earlier than traditional models. In truth, earlier this season, when AI models were quite a bit spicier than traditional models at genesis forecasts, they tended to fail the test. This may also be a case of AI modeling being overzealous for some reason, but it’s something we’ll watch at least. Only 2 known hurricanes have had legitimate hurricane impacts on the Houston area after next week: Jerry in 1989 that hit Galveston and a storm that took a similar track to Beryl from last year that hit in 1949. History is on our side after next week, but as always, we will continue to watch.

For the record, come October we are more likely to be impacted by remnants of Pacific storms that bring heavy rain risk than a direct impact from the Gulf. That can bring its own set of problems, so forecasters stay vigilant deep into October.