In brief: Did you sign up for the Space City Weather e-mail forecasts, but stopped receiving them? Try signing up again, and also check your spam filters! If you think you should be receiving email and you’re not, we’ve got some troubleshooting steps to follow and an address where you can report problems if the troubleshooting doesn’t help.

We’re happy to be able to offer Space City Weather in your inbox as a free service, and we know from direct feedback that thousands of folks in and around the Houston area enjoy waking up to the SCW weekday forecast (at least when that forecast portends fair weather!).

As one of the oldest still-functional components of the modern Internet, e-mail is an ornery technology. Its co-opting by spammers and scammers has led to an ever-evolving series of standards and safeguards that e-mail senders must utilize in order for their e-mails to be delivered successfully. Sending e-mail in bulk—which we definitely do, to 20,000+ subscribers every weekday, and sometimes three, four, or even five times a day during major weather events!—requires strict compliance with a whole bunch of different rules. There are also legal requirements about how unsubscribing should be handled and how e-mail addresses should be stored, and failing to follow the letter of the law here can mean facing penalties under things like CCPA, GDPR, and other acts emerging from the constantly shifting legislative landscape.

Doing e-mail at scale properly, without cutting corners like spammers tend to do, can be very expensive—potentially more than a thousand dollars per month at SCW’s current volume of e-mail. Fortunately for us, we’re able to lean on a service offered by WordPress as part of their Jetpack tool, called “Jetpack Newsletter.” SCW has been using the Jetpack Newsletter service since around 2017 to send millions of subscriber e-mails at a very reasonable cost to us. Jetpack Newsletter also handles the compliance aspect of things, freeing us up to focus on the weather.

Support speaks

However, we receive a small but regular trickle of messages through our “contact us” form from at least one or two folks every week indicating that they at one point signed up for SCW daily e-mails, but stopped receiving them. This has triggered a review on our end of how we’re using the Jetpack e-mail service, and we’ve been discussing the matter with the WordPress/Jetpack support crew.

After some digging, the Jetpack team is confident that the service is working properly and that they’re not unsubscribing anyone unless there are legitimate deliverability problems. I’ll paste in a bit from what they told us in our latest exchange:

At this time, there isn’t a hard limit on the total number of subscribers who can receive your Jetpack Newsletter. While there are limits on manual subscriber imports, subscriptions made directly through your site are not capped, and we don’t offer paid tiers to increase email capacity.

I took a look at your recent activity and can see that your latest newsletter was sent successfully to the majority of your subscribers and opened by over 22,000 recipients. You can confirm this on your end by visiting Stats → Subscribers in your WP Admin.

In most cases where readers stop receiving email notifications, it’s due to their email address being blocked from sending. This can happen for a number of reasons, such as their WordPress.com email notifications being paused, an invalid or outdated email address, marking previous emails as spam, repeated email bounces, or other deliverability-related issues.

Additionally, Jetpack support suggested a few ways (some of which we were previously unaware!) to monitor newsletter sign-ups and newsletter e-mail delivery status from our end, without us needing to open more support tickets.

Next steps for folks still having problems

Armed with these new tools, we’d like to approach the issue systematically. Here’s how.

First off, if you’ve not subscribed to get SCW in your inbox every time Eric and Matt make a post, now’s a great time to do so! You can use the sign-up link in the sidebar on every page, and I’ve also included the same sign-up form right below this paragraph if you’d prefer not to have to hunt for it:

Second, if you’ve subscribed in the past and then stopped receiving e-mails, we’ve got a short list of steps to follow:

- Go ahead and sign up again, using the sidebar form or the form above, to make doubly sure your address is on the newsletter list. (If you’re unsure if you’ve already signed up in the past, signing up again won’t hurt anything or cause you to get duplicate e-mails, so no worries there.)

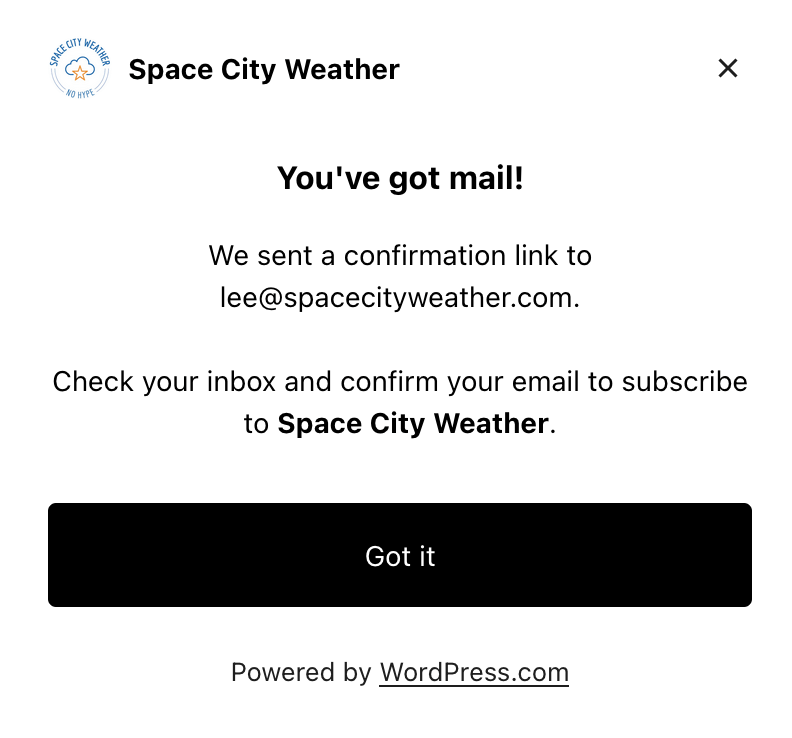

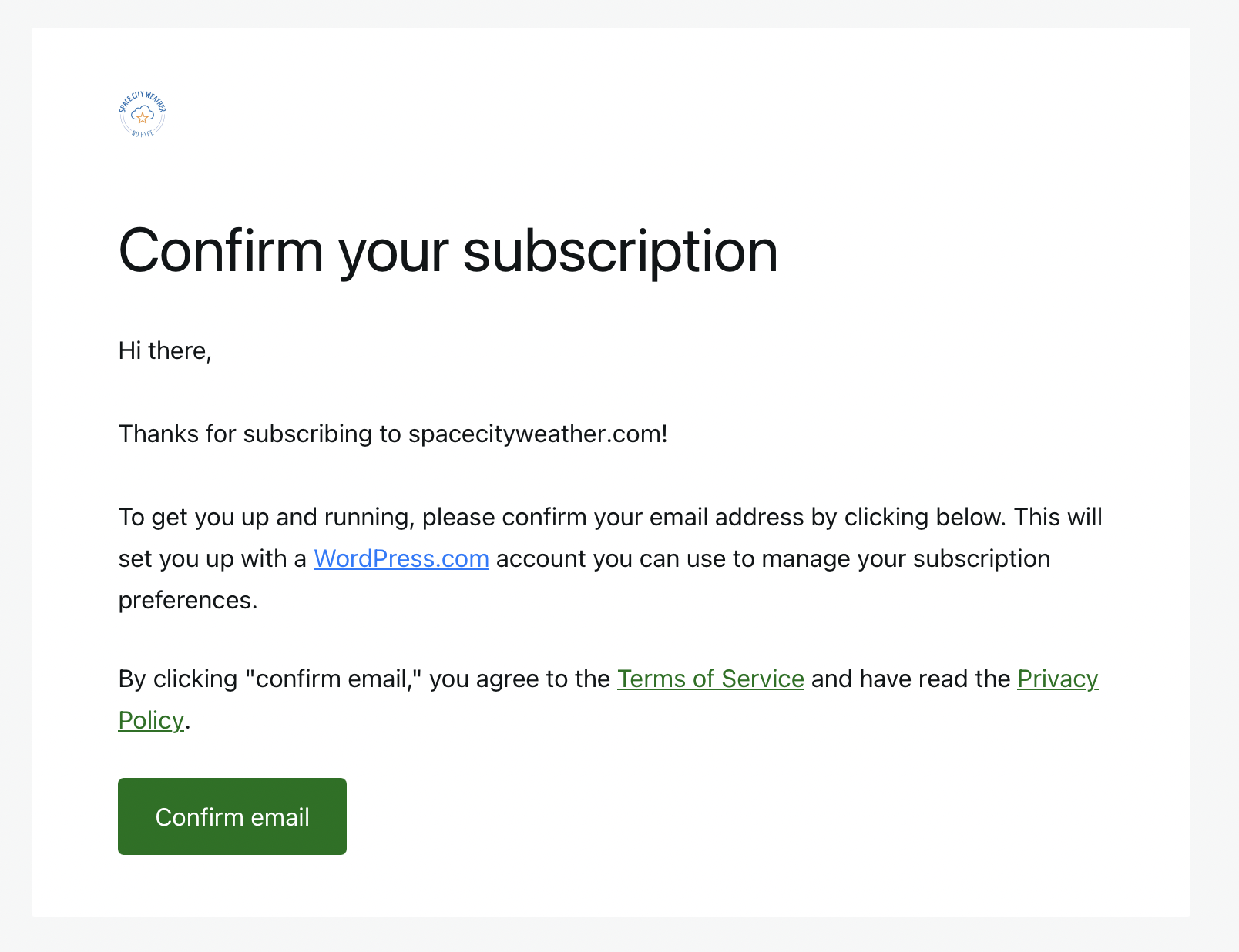

You should immediately see a pop-up dialog box telling you that a confirmation link is on the way. After clicking “Got it” on the pop-up, you should then receive an e-mail at the address you used to subscribe, asking you to confirm your subscription. This “double opt-in” step is mandatory and ensures you weren’t signed up by mistake, and that the e-mail address being provided is valid. You must confirm your address in order to begin receiving SCW e-mails.

- Next, wait a day. Signing up won’t cause any previous e-mails to be delivered, so you’ll need to hang tight until Eric or Matt make their next forecast post. If you’re still not seeing any e-mails after the next day’s SCW post, it’s time to dig a little deeper.

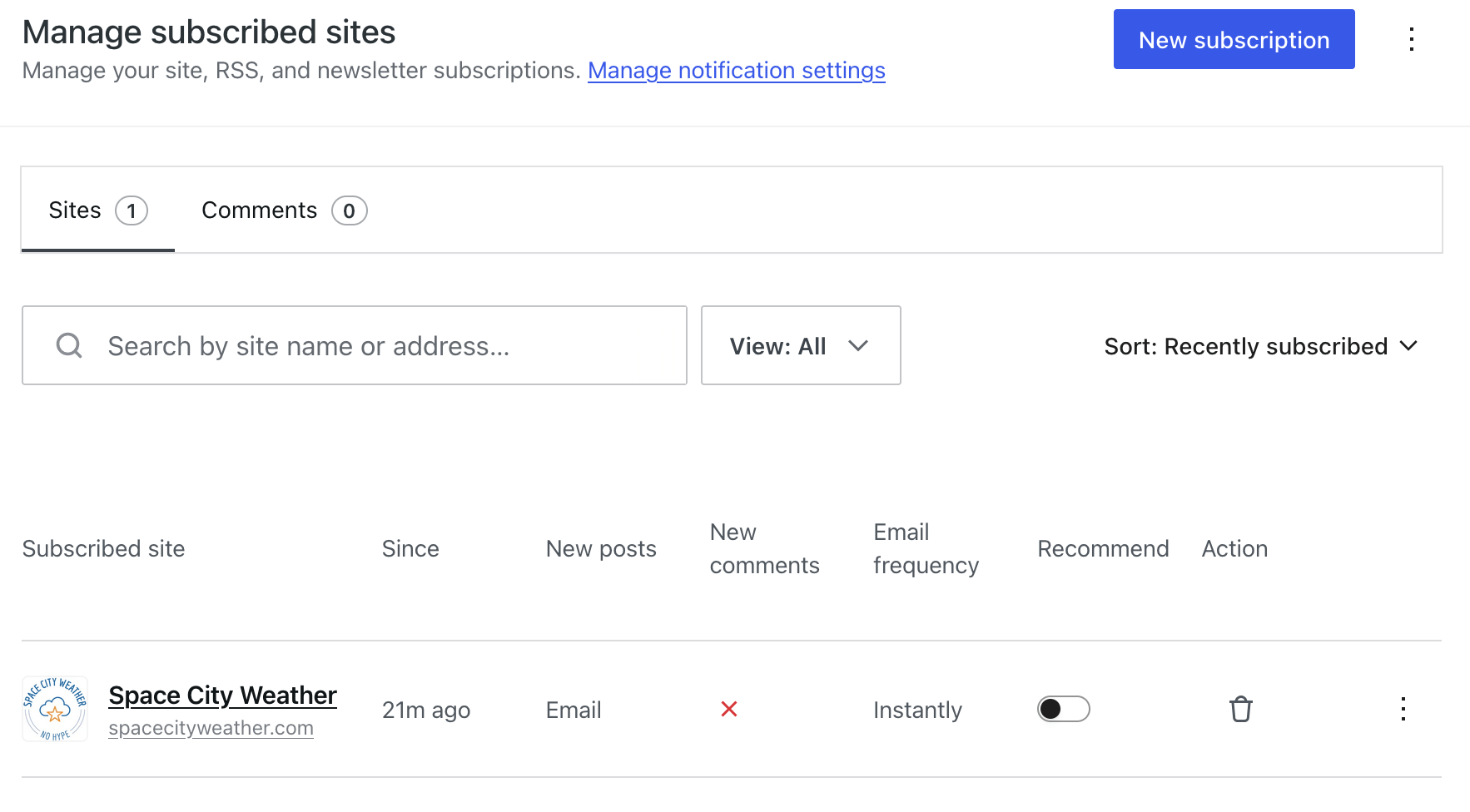

- Check your subscription status on WordPress.com. You can use this link right here to look at the status of all of your WordPress-managed subscriptions, including SCW. If everything’s working, your page should look something like the image below, showing your subscription status:

- Check your spam folder. Because we’re sending e-mail in large quantities, the headers in our e-mails are required to contain metadata explaining that they are bulk-sent newsletters, and how to unsubscribe from them. Some e-mail system spam filters interpret those bulk headers as a sign that the message is probably garbage and that you probably don’t want to see it, and send the messages to your spam folder instead of your inbox. If this is happening to you, explicitly marking one of the e-mails as “not spam” should correct this problem and ensure future messages make it to your inbox.

- Check your “newsletter” e-mail category. Most web-based e-mail providers by default will display newsletters, promotional e-mails, social notifications, and other bulk or transactional e-mails in a separate (sometimes hidden) set of “category” folders unless you tell them to do otherwise. Gmail’s categories can be configured using these instructions, whereas Microsoft O365/Outlook users can check their category configurations here.

- Check your e-mail rules and filters for anything that might be routing e-mails away from your inbox. How to do this varies by e-mail provider and even by the e-mail program you’re using. Gmail’s instructions are here; Microsoft’s are here.

If all else fails…

If you’ve verified that you’re signed up and your subscription status looks good, and you’ve checked your spam folder and your filters and your category lists and you’re certain everything is set properly, and after all that you’ve still not received any forecast e-mails, then we definitely want to hear from you so that we can investigate with our new tools!

For folks in this unfortunate situation, please end us a note at [email protected] and let us know. It is vital that you include in your note the e-mail address with which you’ve attempted to subscribe! Without that, we’ve got nothing to search for in the logs and we won’t be able to help.

Please also understand that we have a technical team of precisely one person—me!—and I might not be able to respond the same day. But even if it takes a bit of time to get back to you, please know that we’re looking at every report that comes in to see if there are any problems or issues we can fix on our end.

Thanks for choosing to be a Space City Weather reader. Stay warm out there!