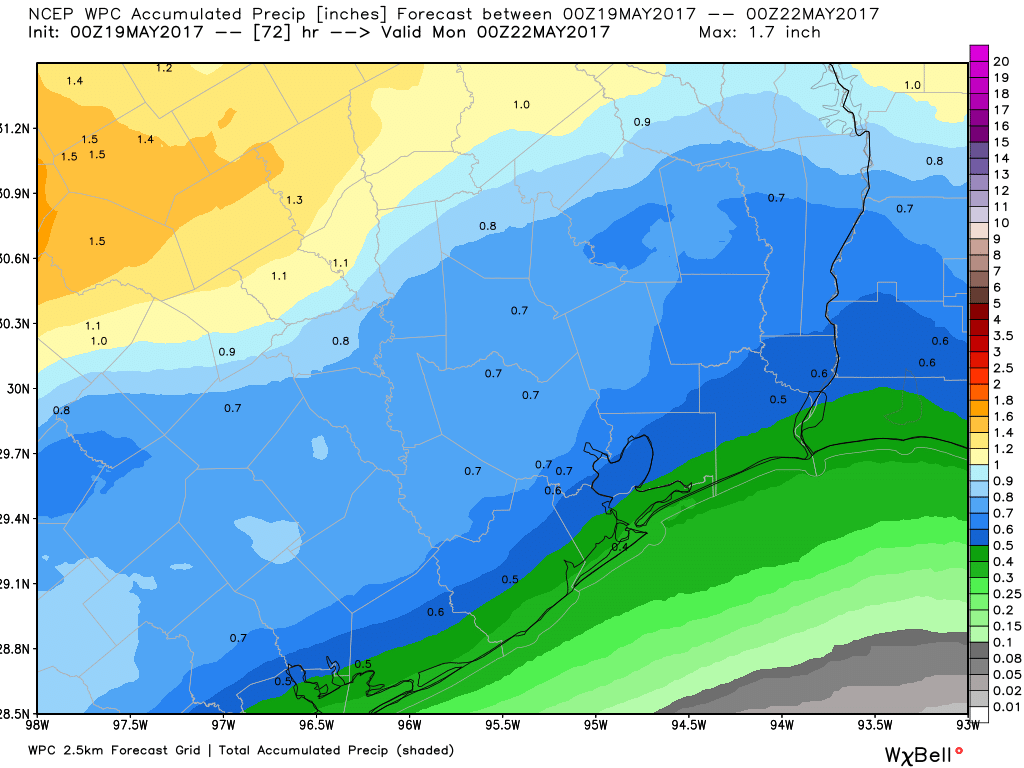

As anticipated, widespread showers and thunderstorms have moved into the Houston area this morning, particularly affecting the coastal regions. Due to the storms, the southern half of the metro area is under a flash flood watch through 1 pm.

Monday

As an upper-level disturbance moves in from the southwest, it is combining with high atmospheric moisture levels to continue to bring a healthy chance of rain into early afternoon hours. However, the large cluster of storms is moving slowly to the east, and therefore should clear the area by some time this afternoon.

For the most part, given our relatively dry ground, rainfall amounts should be quite manageable—1 to 3 inches along the coast, with lesser amounts for inland areas today. We’ll have to be concerned about the possibility of some locally heavier rainfall, but so far these storms have been manageable. Highs should be around 80 degrees.

Tuesday

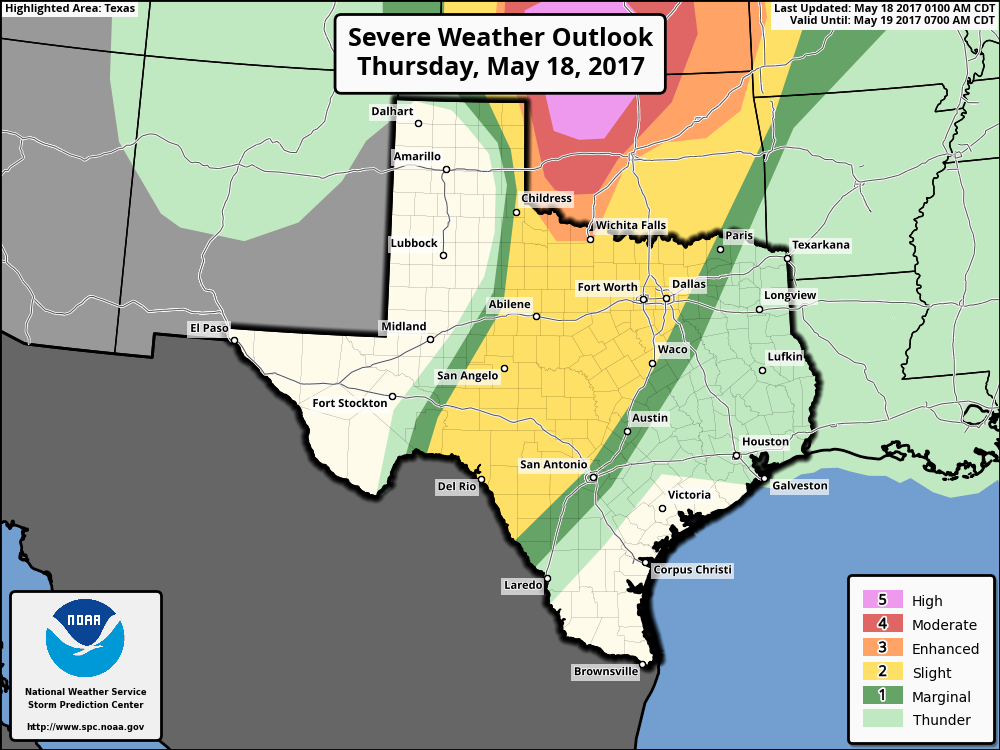

Rain chances drop off Monday night and Tuesday morning, but then a late-season cool front will move through the region sometime during the day. This front will bring enough instability to produce some scattered showers and potentially thunderstorms (very slight chance of severe weather) later on Tuesday. Rain accumulations will certainly be less than today, and areas that see rain probably will only see a tenth of an inch, or two.

(Space City Weather is sponsored this month by Jetco Delivery)