For those able to enjoy weekends, congratulations. For the third weekend in a row, we are expecting just stunningly beautiful, chamber of commerce type weather.

Fundraiser

I just want to echo Eric’s sentiment this week, and I want to thank everyone who has been so generous during our annual fundraiser. We sincerely appreciate you, and we are truly humbled by your support. The fundraiser continues for another 18 days, and we’ve got some cool options available here. You can read more from Eric’s post on Tuesday here. Thank you, truly.

Today through Sunday

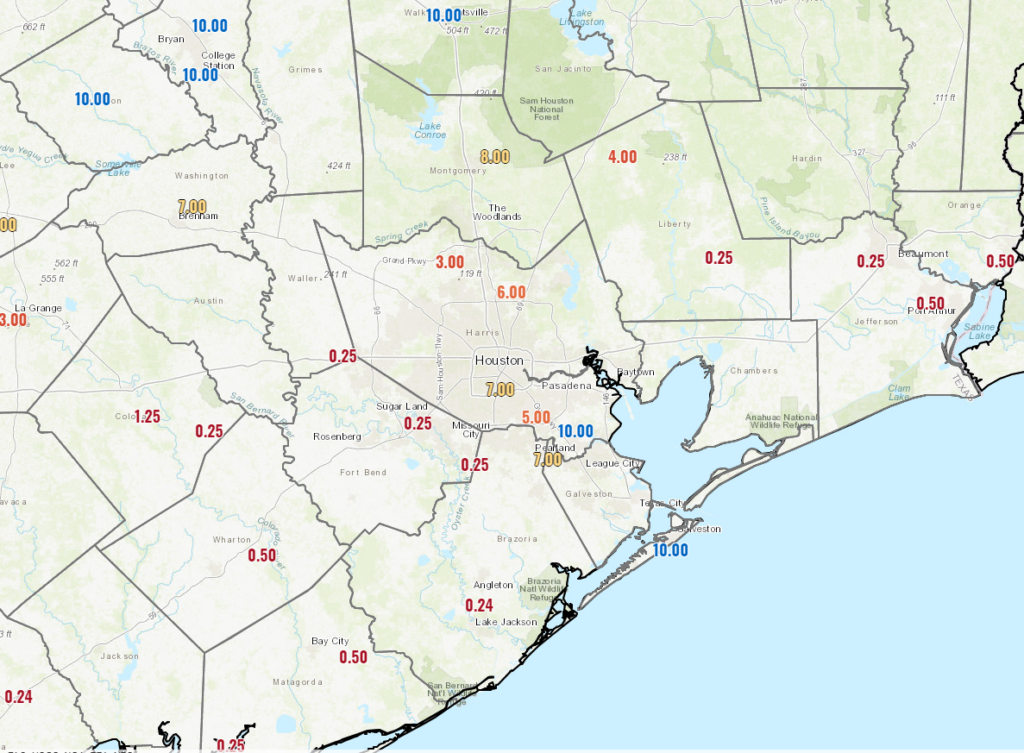

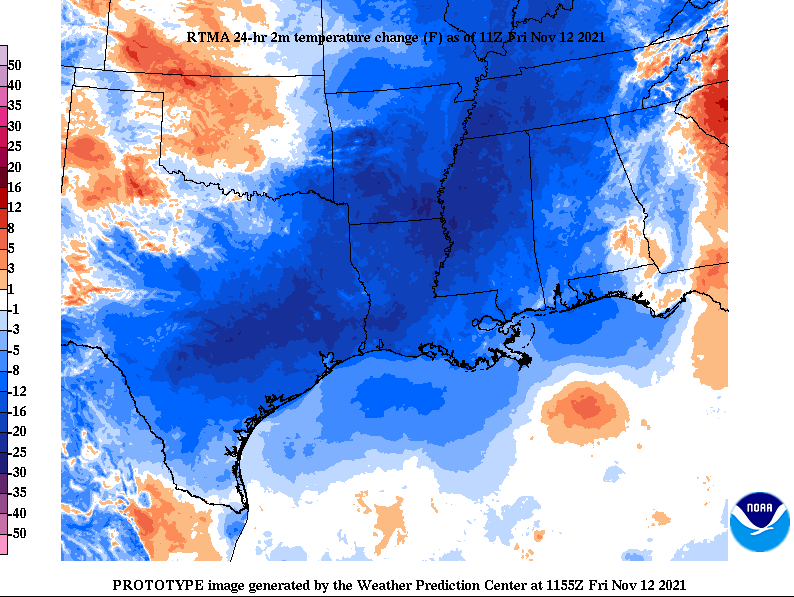

Temperatures this morning are noticeably cooler than they were 24 hours ago.

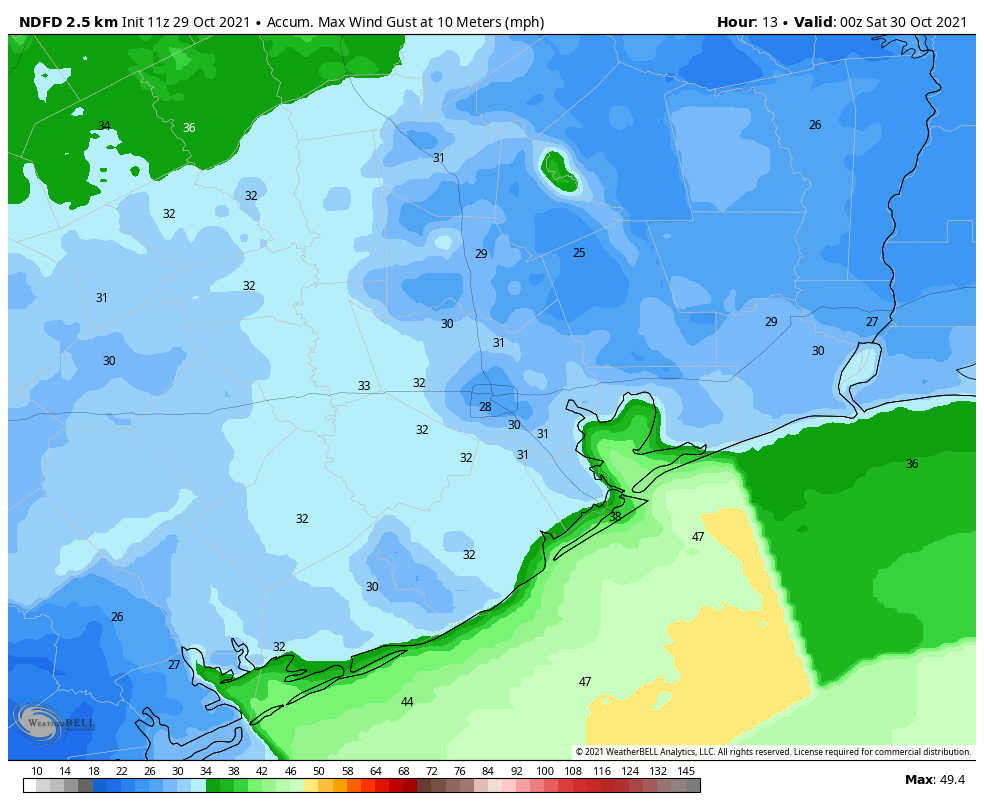

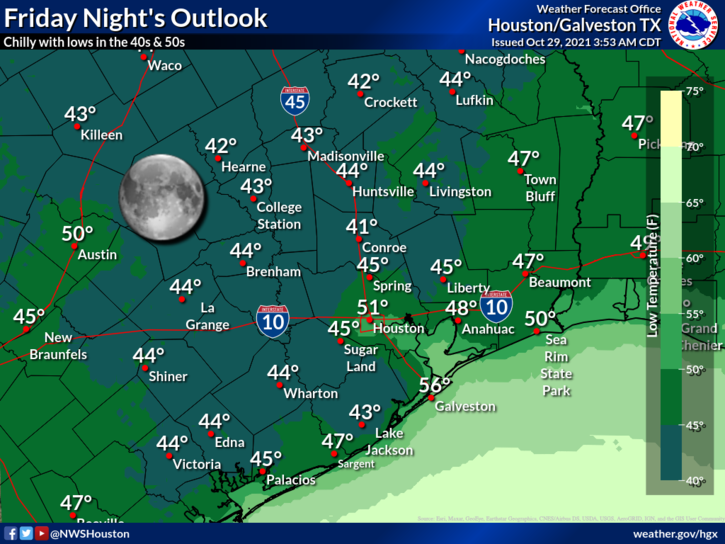

It’s a refreshing start to the day, with 40s and 50s in most spots and 60s along the coast. We’ll see ample sunshine with highs well into the 70s today. We had a cold front yesterday, but it’s still going to be a little warm this afternoon, so what gives? Yesterday’s front was more of a humidity front than a true cold front, so it ushered in drier air for today but the air mass wasn’t really a lot cooler. If you took the temperature about 5,000′ over our heads, which is a good altitude to look at to define the “air mass,” today is only about 3 or 4 degrees cooler than it was yesterday. But it was the dry air that helped allow temperatures to drop more this morning. Now, a secondary front is going to usher in the notably cooler air tonight. That air mass 5,000′ over our heads will drop about 10 to 12 degrees behind that front. This second front will have no moisture to work with, so no rain is expected, but winds may pick up just a bit after it passes and linger into Saturday.

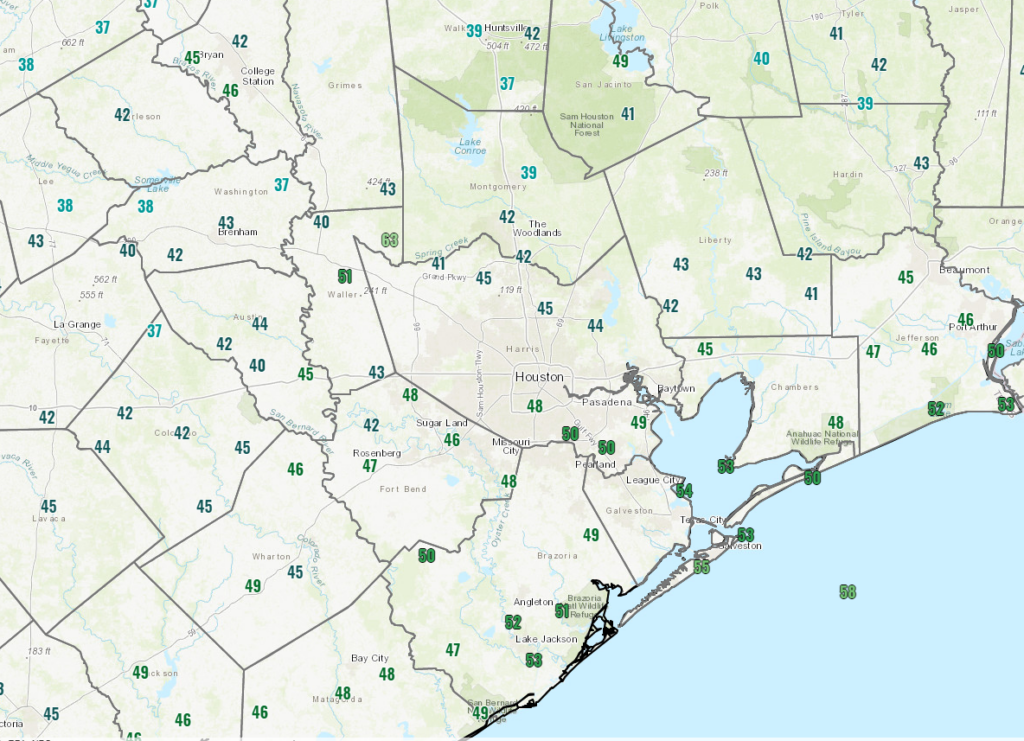

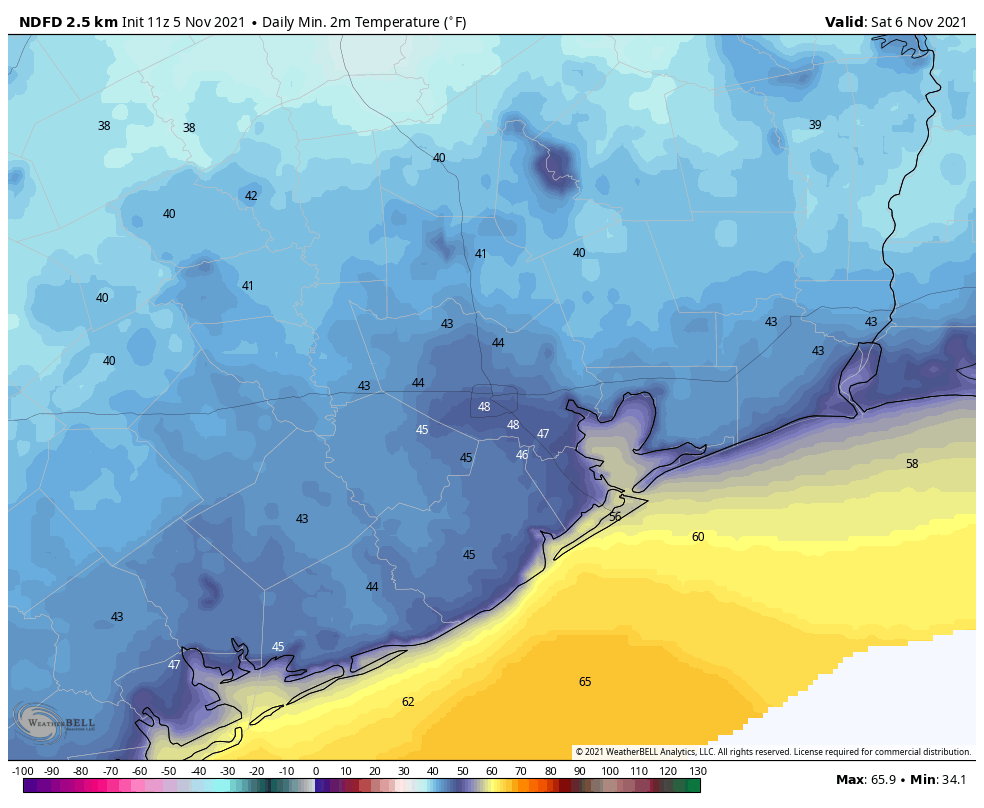

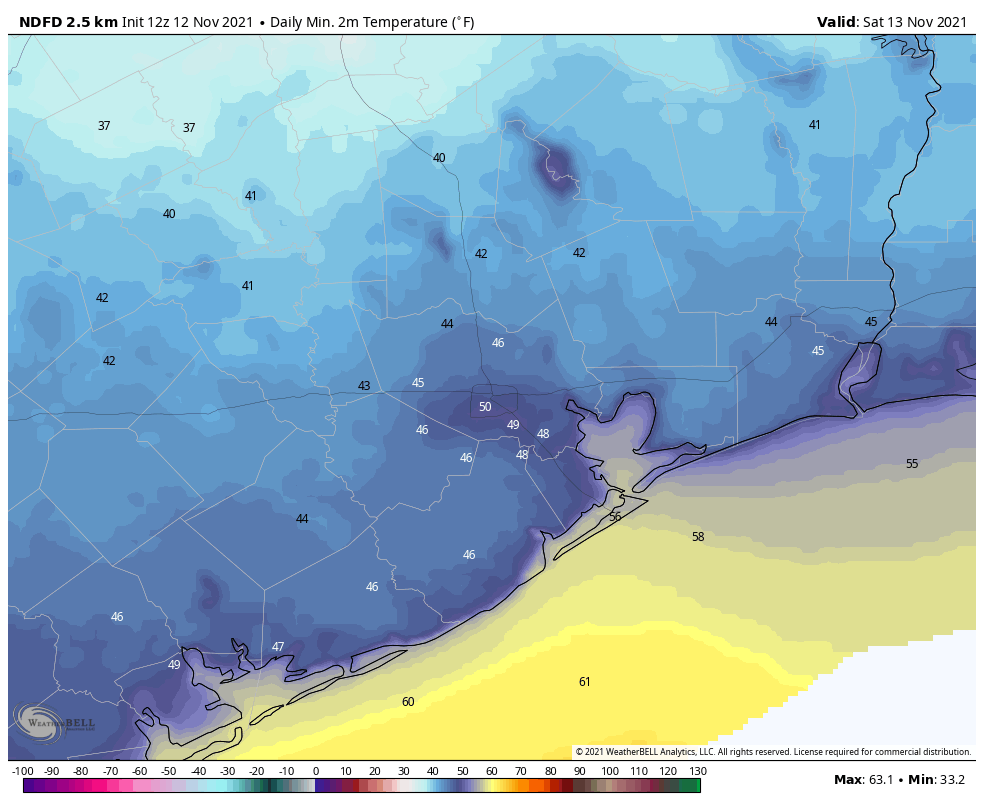

That secondary front will allow temperatures to dip into the 40s tonight across most of the area.

Saturday should be another beautiful day with full sunshine. Temperatures will be noticeably cooler though, with highs only in the 60s. Look for mostly a rinse and repeat on Sunday, with morning lows in the 40s and a slightly warmer afternoon around 70° or in the low-70s.

Monday

Look for the time honored tradition of onshore flow to resume sometime on Monday. Initially, the day will start cool once again, with 40s or 50s across the region, but we’ll warm into the mid-70s in most spots during the afternoon.

Tuesday and Wednesday

Onshore flow will likely strengthen some here as a fairly tight pressure gradient boosts southerly winds a bit. Tuesday should start in the 50s to near 60, then warm deep into the 70s with sunshine. An 80 degree reading can’t be entirely ruled out in spots on Tuesday afternoon. By Wednesday, look for higher humidity to have fully taken hold with a warm morning (60s) and a rather warm afternoon (80 degrees or better). We should also begin to see a few more clouds by Wednesday.

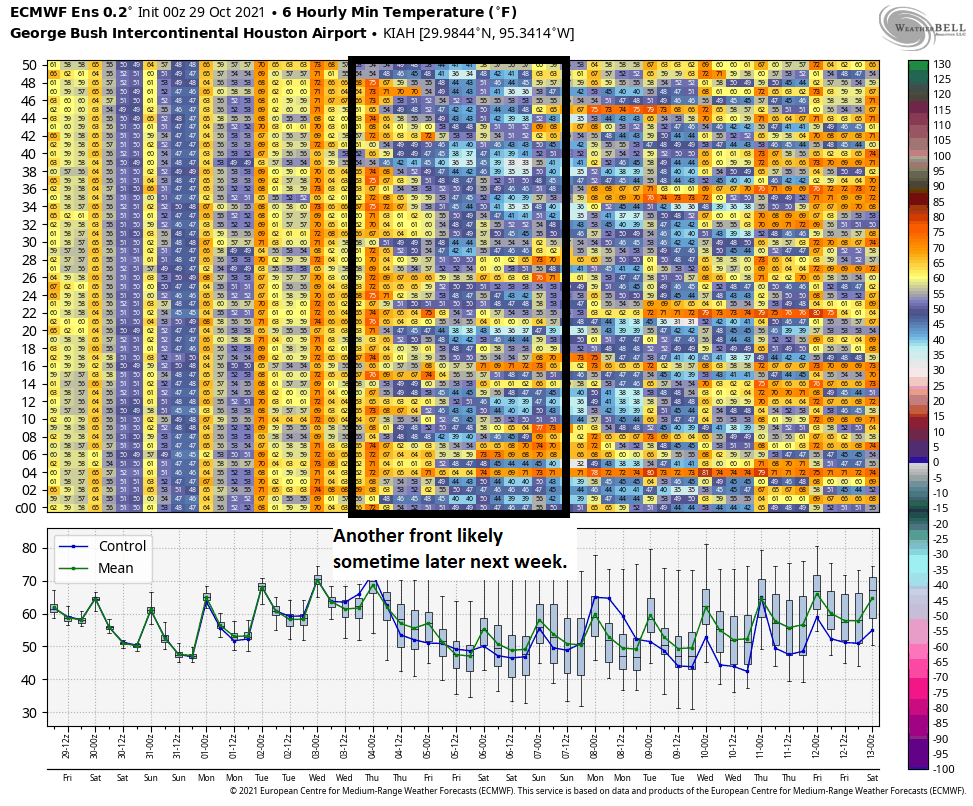

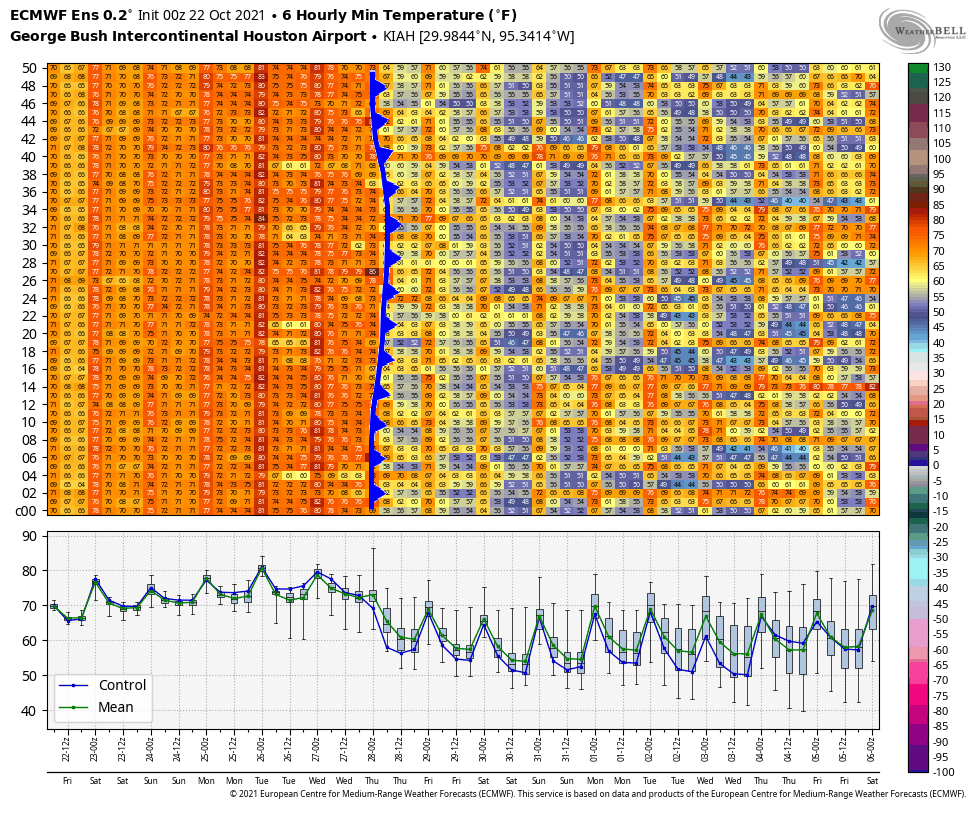

Beyond Wednesday

The forecast after Wednesday begins to get a little difficult. I think we should see a cold front arrive sometime around Thursday or Friday, but what happens after that front gets through is tough to say. I’m not sure we are going to lock in a fourth consecutive gorgeous weekend, though that’s not an impossibility. But it would appear another front or two could be in the mix heading into Thanksgiving week, with perhaps the strongest one yet just prior to the holiday.

The usual doomsayers have been spreading rumors and such out there on YouTube and Facebook/Meta about “the polar vortex,” among other nonsense. Quite frankly, nothing we’re seeing in the Thanksgiving week timeframe looks that remarkable. As our average temperatures drop and the fronts get a little stronger, perhaps we could see our first official 30s of the season show up sometime Thanksgiving week. It’s far too early to say that will happen with any confidence though. And anything worse than that seems highly unlikely. The average date of our first sub-40 degree temperature in Houston is November 17th, so that would actually be close to normal. We’ll keep you posted.