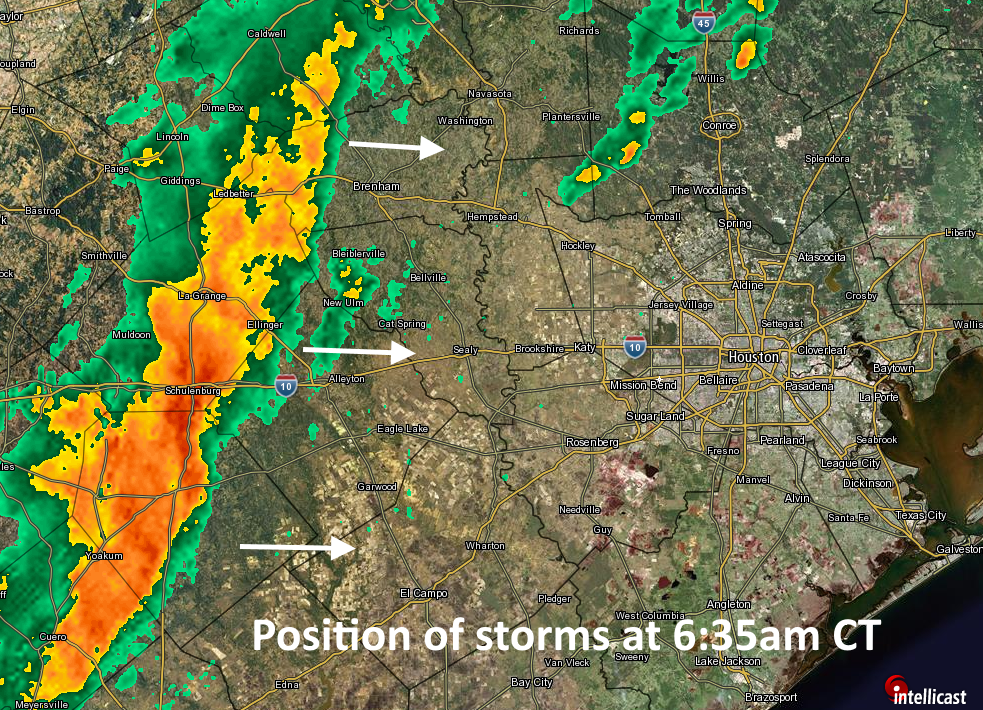

Good morning. The big concern today is a line of strong thunderstorms moving into metro Houston this morning from the west. As of about 6:30am CT, the leading edge of the main line of storms was located at Schulenburg.

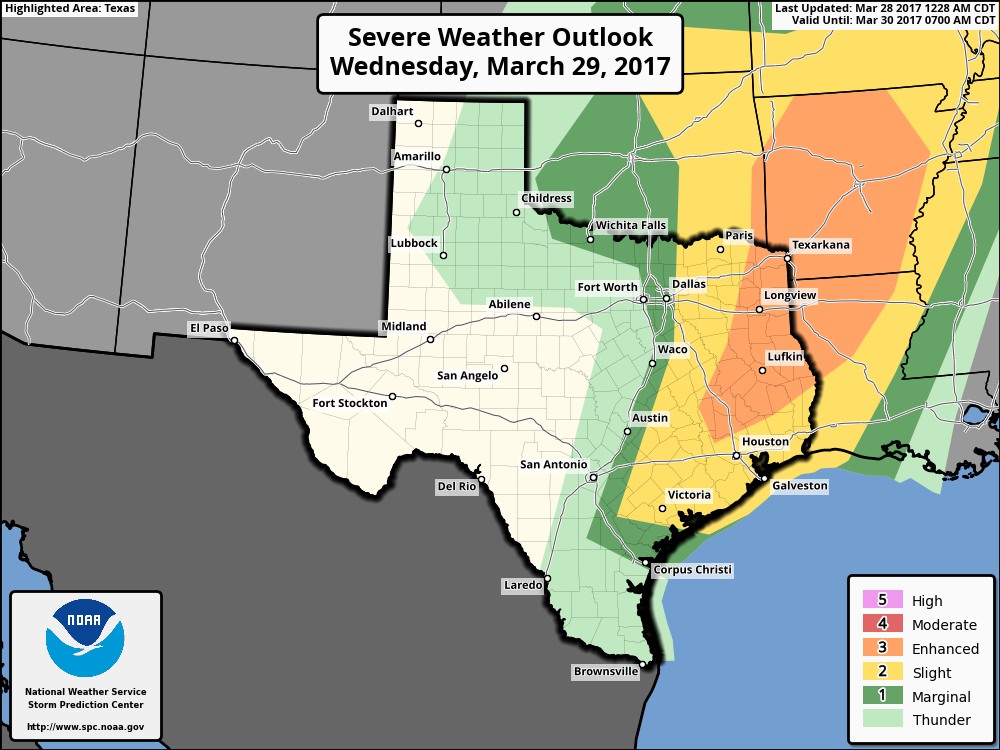

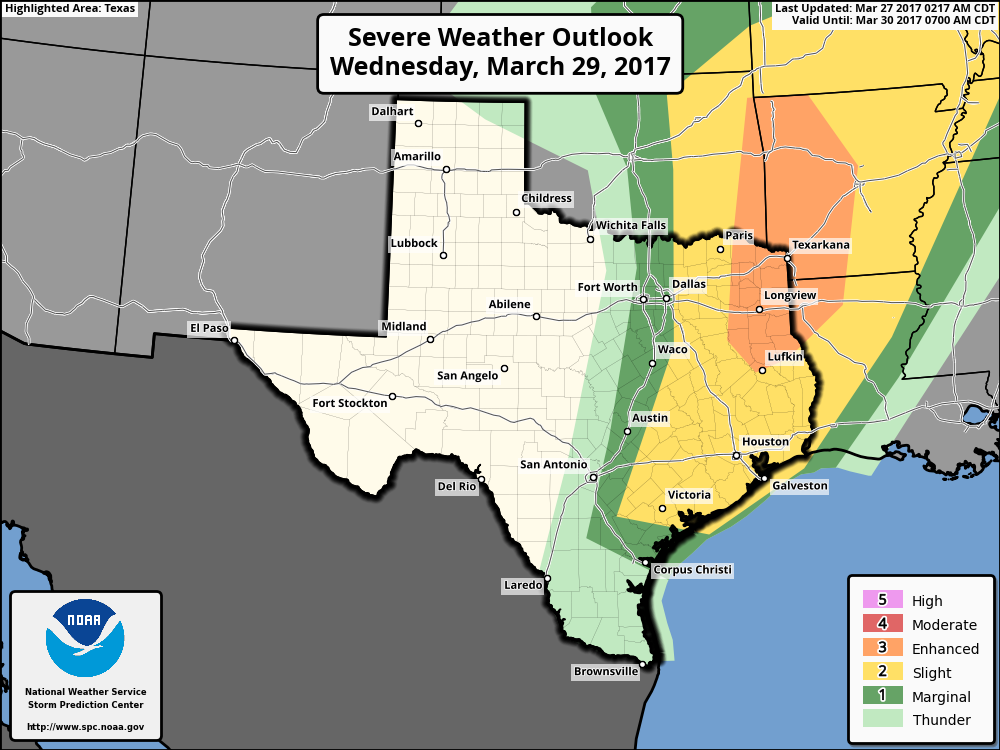

These storms will advance into Houston later this morning, likely reaching western parts of the metro area between 7 and 9am CT and moving into the central Houston area by 8 to 10am. The main threats from these storms include damaging winds (gusts of 40mph or greater), heavy rains, and possibly some tornadoes. As these storms have moved across central Texas they have produced a large amount of lightning, and briefly torrential rain has caused some short-lived street flooding.

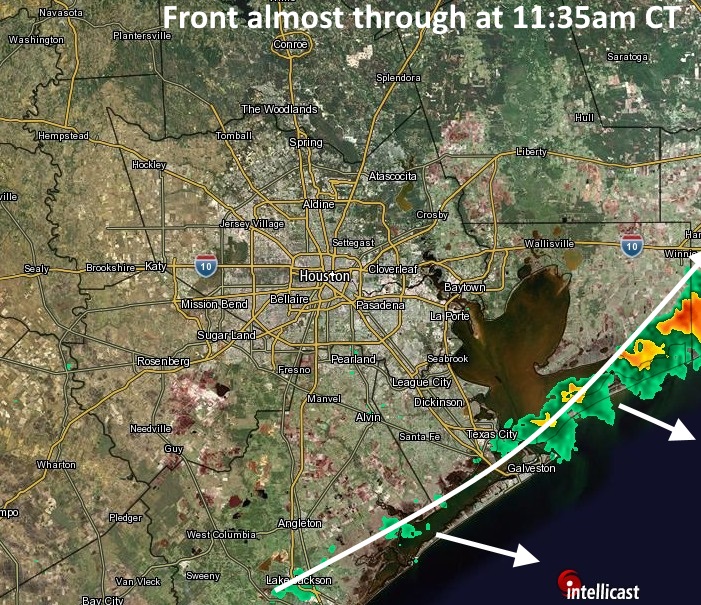

Fortunately, the storms are moving to the east at a good clip, may weaken a bit as they approach the coast, and should pass through most areas in about an hour. After the main line moves through this morning, some additional, lighter rain may linger across parts of Houston this afternoon and evening, before a cold front moves through tonight. This should lead to briefly cooler weather on Thursday—it’s going to be a spectacular day, plan to spend some time outdoors if possible—before we warm up again heading into the weekend.

After sunny conditions Saturday, we’ll again have to watch for the possibility of heavy rain on Sunday, although models have backed off some of their extreme predictions. I’d still expect a solid 0.5 to 1.5 inches of rain on Sunday and Sunday night for the metro area, and conditions will again be in place at least for the possibility of some severe thunderstorms.

Posted at 6:45am CT on Wednesday by Eric