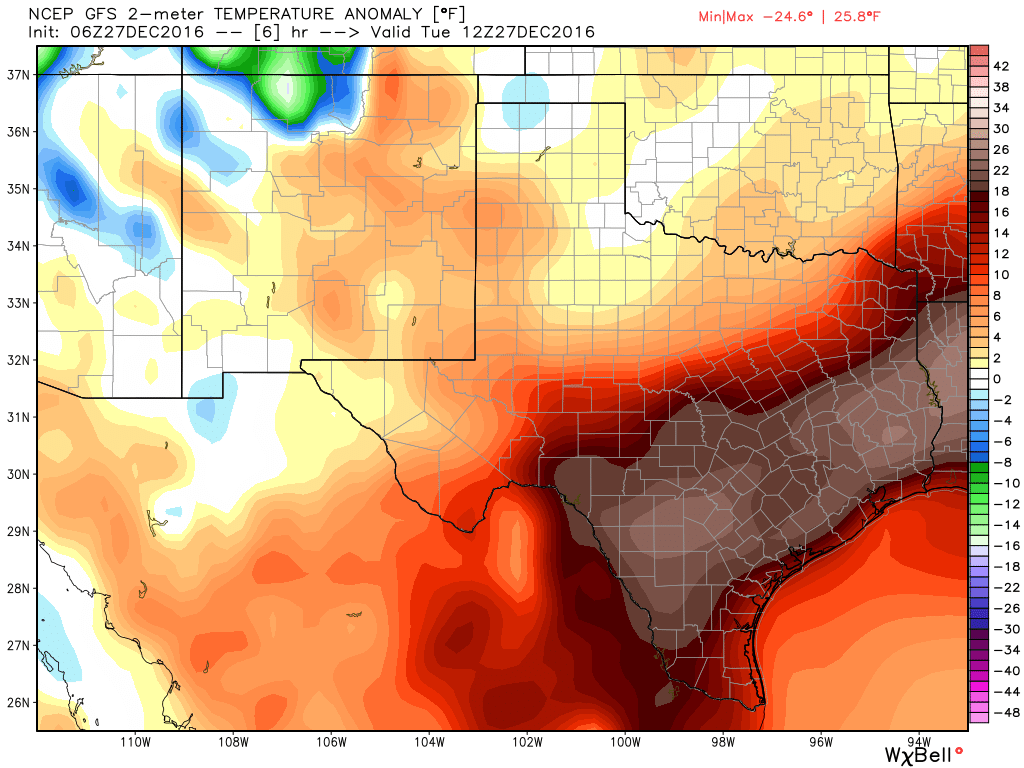

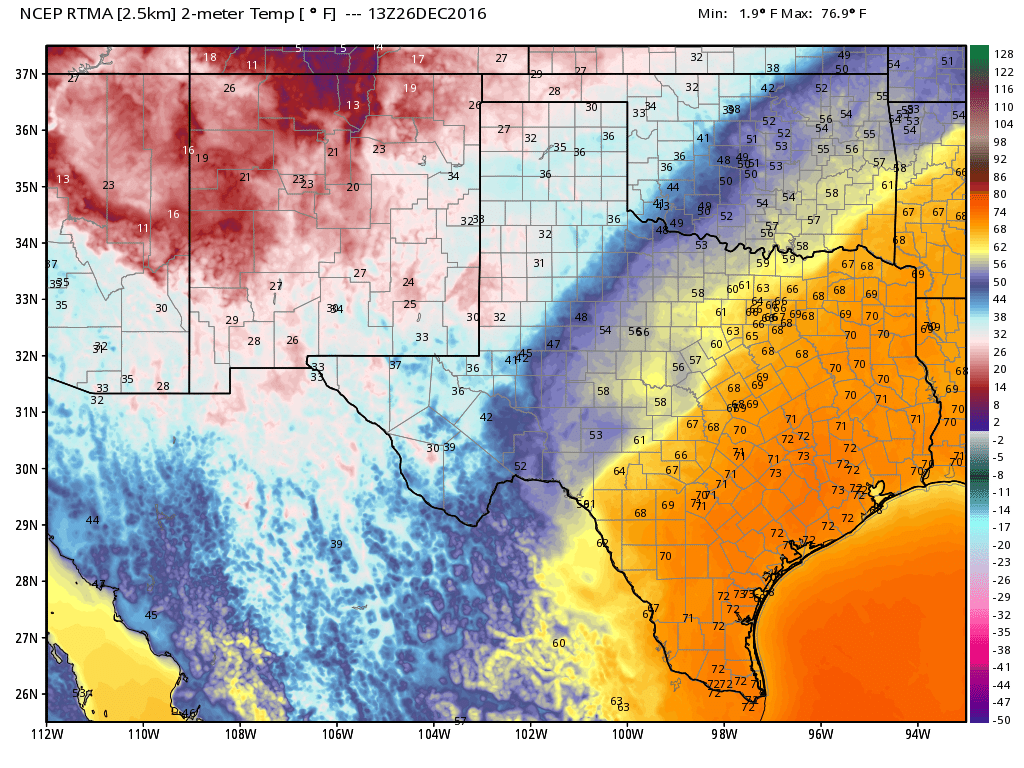

This month’s anomalously warm weather continued on Monday, with a record high of 84 degrees. How abnormal is that? Just one day—one single day—has been warmer than that in all of the Decembers in more than a century of weather records of the city (Dec. 3, 1995, 85 degrees). The average temperature on Monday, 78 degrees, was 25 degrees above normal. Fortunately, this can’t, and won’t, continue for much longer.

Today

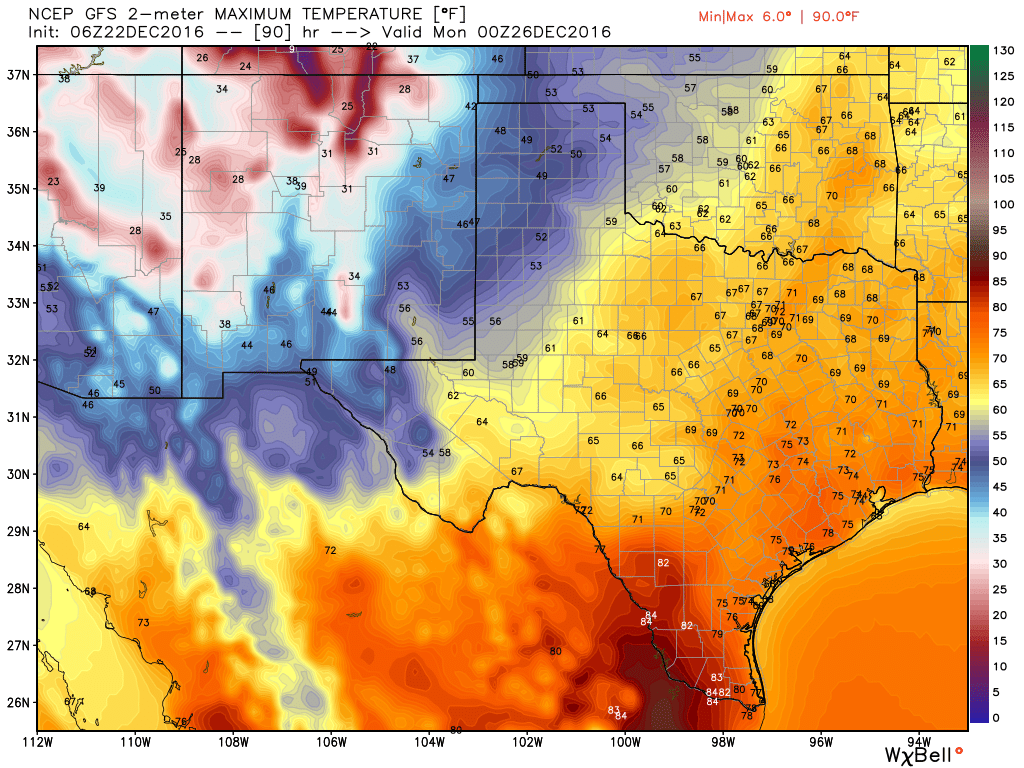

After a foggy start this morning (a dense fog advisory remains in effect until 9am CT), highs today should max out in the upper 70s. Mostly cloudy skies, and some scattered showers, should limit temperatures more than anything. A front will approach the region from the northwest, but should stall out before pushing into the city itself. This should help lows fall into the mid-60s tonight.