As most Southerners know, the arrival of spring also means the arrival of severe weather season. On Wednesday morning, many Houstonians heard the first rumblings of serious thunder for 2018, and if history tells us anything, this is just the beginning of a potential spring full of thunderstorms, flooding, lightning and tornadoes. What is it about the springtime that initiates this activity?

Hot, Hot Heat

Thunderstorm formation depends on atmospheric stability. We’ll forego talk about lapse rates and latent heat for now, and describe stability in simple terms. During the wintertime, our atmosphere is generally very stable. This means that conditions in the air prohibit any vertical motion. For thunderstorms to develop, they need warm air to rise from the surface, then to cool and condense into a tall, vertical column of clouds. In a stable atmosphere, this is nearly impossible.

As winter turns to spring, two things occur that make the atmosphere much more unstable. First, the air around us, especially if that air comes in from the Gulf, becomes much warmer and much more humid. Yesterday, February 20th, Bush Intercontinental Airport recorded a high of 80°F, with relative humidity values staying above 70%. This warm, moist air mass created a perfect environment of instability around us.

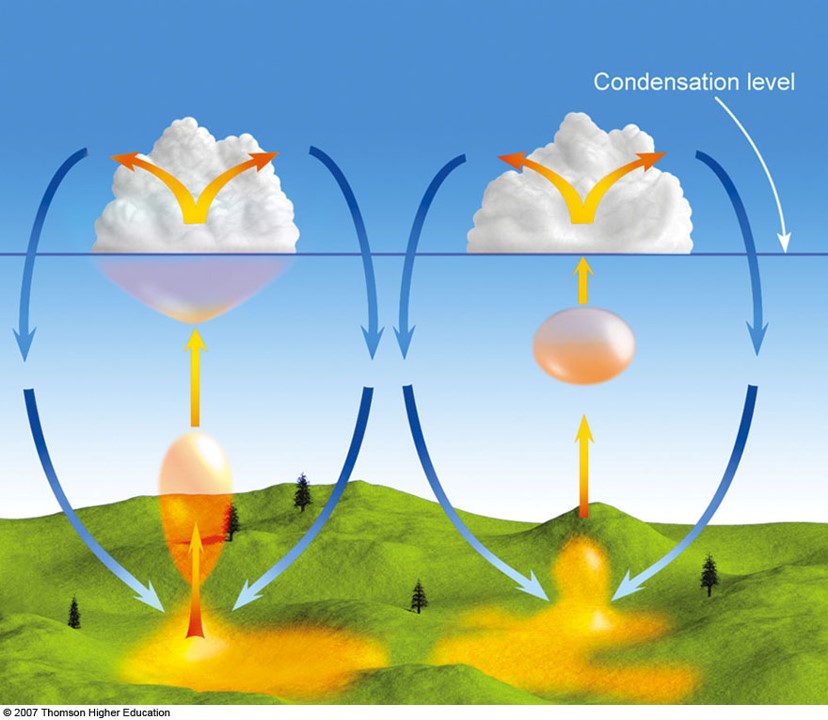

Second, as days become longer and the sun rises higher in the sky, the sun heats the ground, which, in turn, heats the air directly above the ground. This warm air will eventually rise in an unstable atmosphere, pushing cold air out of the way, as the diagram above shows. As it goes up, the air begins to cool, and as it cools, the water vapor in the air will condense–into clouds! If the atmosphere remains unstable, and these pockets of warm, condensing air rise rapidly, we have the recipe for a thunderstorm.