To close out 2020, Eric and I put together two posts to summarize the Atlantic hurricane season, its effects on Houston, and implications for the future. Eric wrote Part I yesterday, which discusses the overall season and Hurricane Laura in particular. In Part II, today, I will discuss Tropical Storm Beta and what we can learn from this season about future hurricane activity.

Tropical Storm Beta

While Hurricane Laura was a clear and definitive threat, Tropical Storm Beta was a more difficult nut to crack. From the outset, we weren’t so much concerned about Beta as a wind threat, but rather as a slow-moving, disjointed storm capable of producing prolific rainfall. The tropical update I wrote back on September 15th discussed future Beta as an “untagged” disturbance that probably was more a concern for South Texas. “So while we aren’t particularly worried about this area, we do feel it’s one to keep an eye on.”

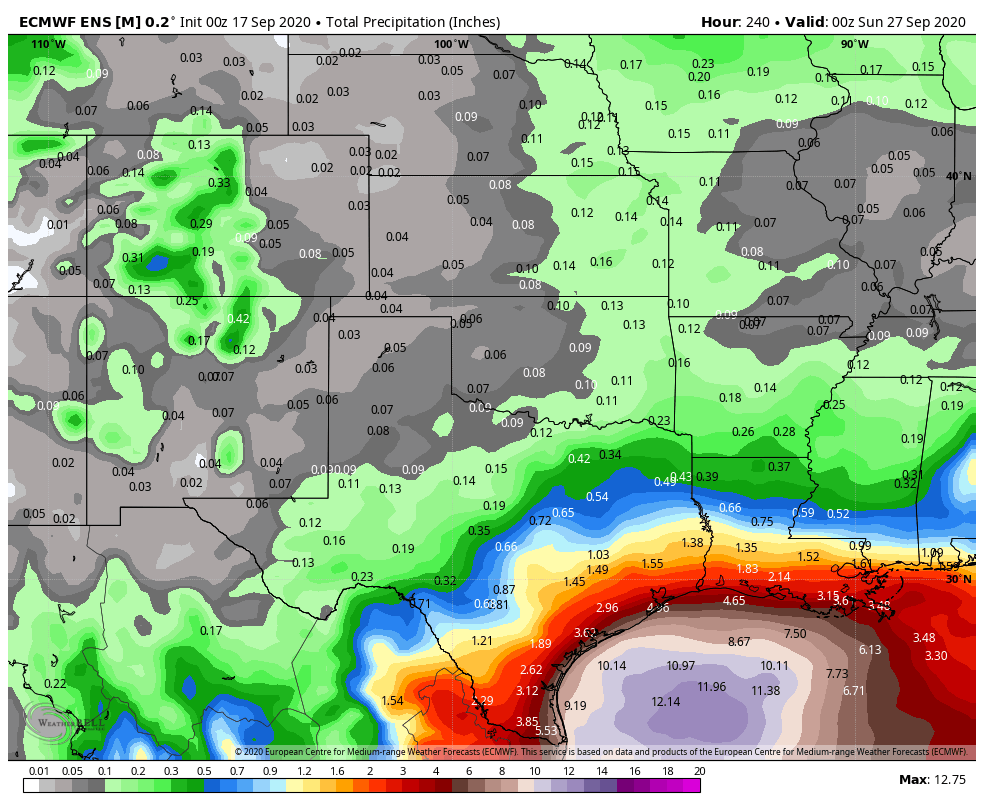

The issue with Beta was rainfall, and you could see a strong signal several days beforehand that it had the capability of producing double digit totals, as seen below from our Thursday morning post.

By that Thursday afternoon, a Tropical Depression 22 had formed, and modeling began to suggest it would come farther north. Our first real early season cold front around that time would help keep most of the rain offshore, but there were indications that the system itself could make a run at the Texas coast on its way out, moving slowly and dumping rain on the way.

Initial rain forecasts began circulating on Friday as Beta’s track came more into focus, with as much as 10 to 15 inches forecast along the coast south of Houston. We also began playing up the coastal flooding risk posed by Beta. By Friday afternoon, we had classified Beta as a Stage 2 flood risk (south of I-10) using our SCW Flood Scale.

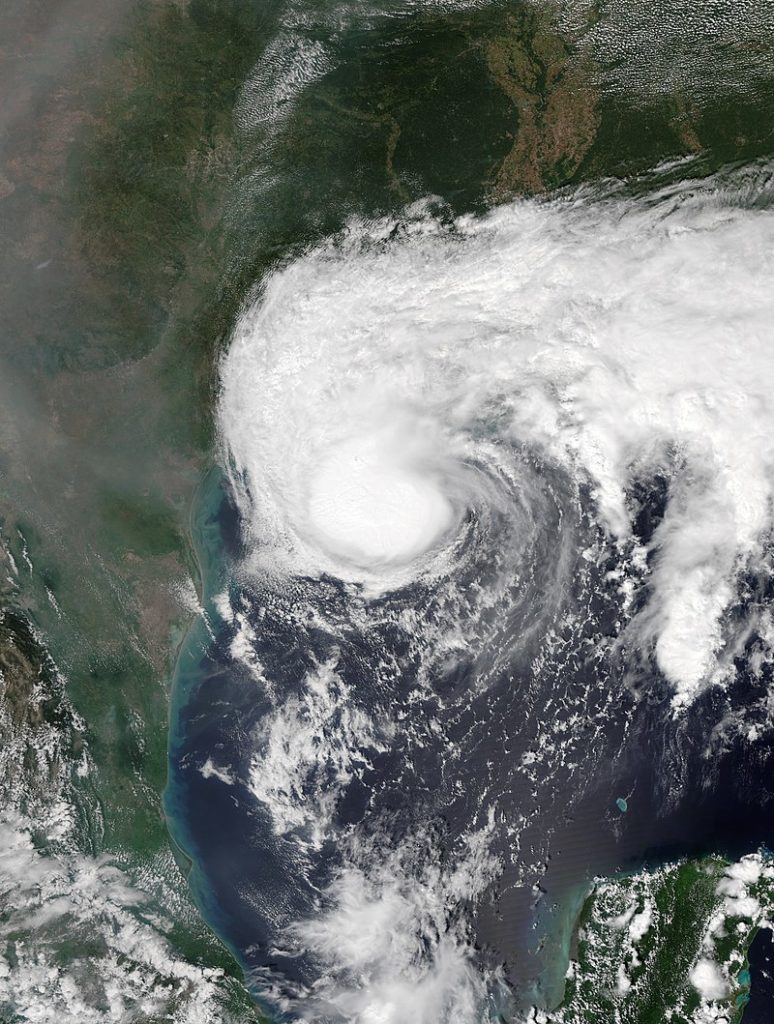

On Saturday, we got a good handle on the general theme of how Beta would unfold, likely as a rainfall issue but not too terribly serious, some wind but not so much to cause widespread power outages, and considerable coastal flooding. Beta reached peak intensity over the Gulf on Saturday, though at the time, it was still expected to become a hurricane upon approach to the middle Texas Coast.

Beta’s rainfall was expected to still be pretty aggressive, with upwards of 4 to 12 inches expected and at least the risk of 10 to 20 inches in a worst-case scenario.

We knew it had potential to cause headaches, but we did not feel it was going to become a catastrophic storm.

By Sunday the 20th, I began to check out because becoming a second-time dad took some precedence. But the rains began as Beta tracked toward the coast near Matagorda and then along it to the northeast through Houston. On Sunday, about 1 to 2 inches fell across eastern and southern Harris County and northeast parts of Fort Bend County, mainly near Sugar Land. Beta tried valiantly to strengthen on Sunday afternoon but failed.

Monday saw Beta begin its peak assault on the Texas coast, with heavy bands of rainfall setting up over and south of Houston by evening. Close to 10 inches of rain had fallen south of Houston, causing some bayous to come out of banks. Rain continued off and on into Tuesday morning, leading to more widespread flooding that caused us to escalate things to a Stage 3 flood event south of I-10. Thankfully, the rains tapered off a good bit on Tuesday, and the heavy rain on Tuesday night setup a bit farther northeast than Monday night, allowing for less flooding problems. By Wednesday, Beta had moved away, and that was that.

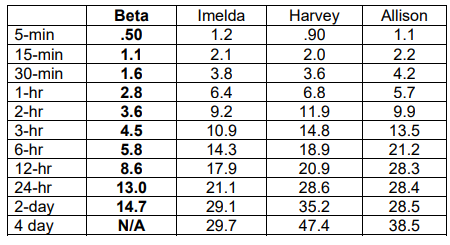

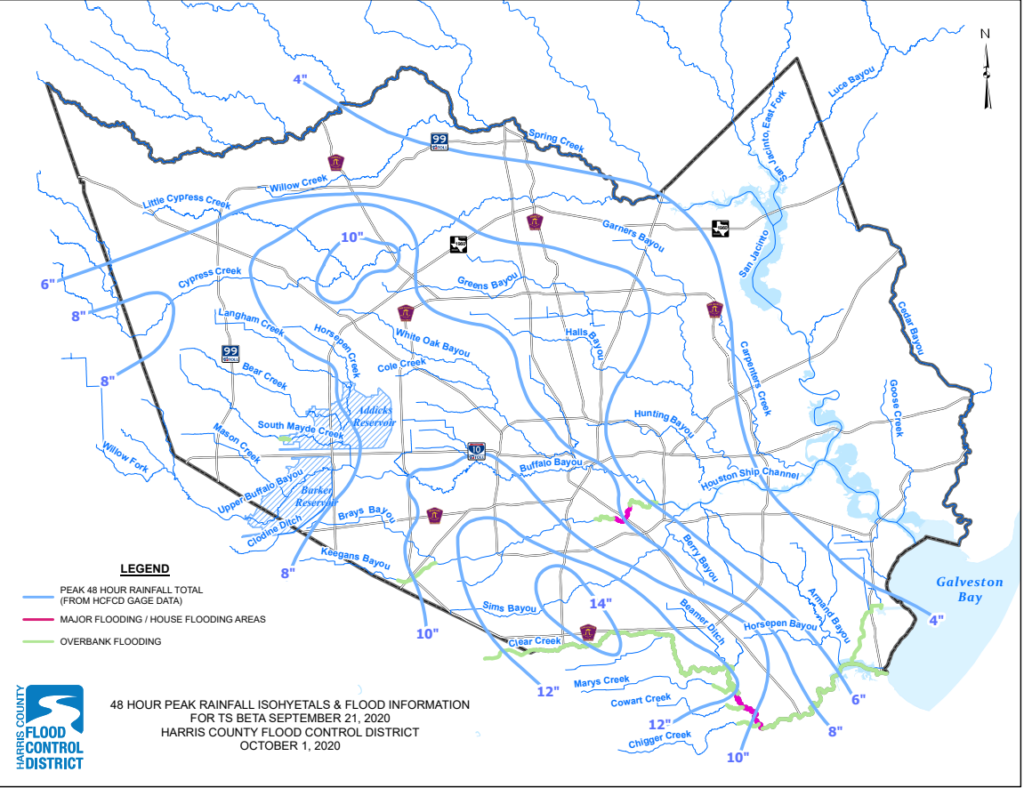

From a return-period standpoint, Beta’s 48 hour total rains were mostly classified by the Harris County Flood Control District as between a 2 and 10-year event (or a storm that has anywhere from a 10 to 50 percent chance of occurring in any given year). The lone exception appeared to be portions of Sims Bayou that may have been closer to a 50-year type of storm, meaning in any given year there’s about 2 percent probability that we’ll exceed certain rainfall totals. You can see that while Beta was certainly a respectable storm, it paled in comparison to our recent major flooding events from tropical systems.

Beta flooded 20 to 25 homes along Clear Creek or Brays Bayou and a handful of homes (due to drainage) near the South Loop at Cullen. Because the maximum rate of rainfall during Beta was “only” about 2 to 3 inches in an hour, and there were breaks, the area was able to mostly avoid severe, widespread bayou and/or home flooding. Harris County Flood Control estimated that nearly 1,000 homes were spared flooding due to recent capital improvements along Brays and Sims Bayous.

As far as storm surge and coastal flooding went, the other element of this storm, it was estimated that surge levels hit 1 to 4 feet above ground level along the western shore of Galveston Bay and on the Gulf Coast, a firm moderate coastal flooding event for many areas.

Laura reminded us of our exposure and vulnerability to a major hurricane, while Beta was a good reminder of the rainfall hazards we must accept by living in this part of the world. While storms like Allison and Harvey are thankfully rare (though perhaps becoming less rare as time goes on), storms like Beta, which produce heavy rainfall and sub-catastrophic flooding, are pretty typical in Texas, which sees slow-moving tropical systems fairly frequently. Again, this may be occurring more frequently as climate change impacts become more common. It’s important to have flood insurance if you live in this area, and it’s important to have a plan if flooding from rain or bayou rises impacts your home.

For those that utilize our Space City Weather flood scale, Beta will go in the books as a lower-end Stage 3 flood. While it may have fallen in between stage 2 and 3 to some extent, given the widespread flooding we experienced and coastal impacts, we feel a low-end 3 makes sense. If you read about the historic Stage 3 examples, we would probably rank Beta just under all of those listed.

The future

The first question we expect to be asked is, “Does the fact that this hurricane season was so active mean next season has higher odds of being more active also?” And we would say, it absolutely does not mean that.

The 10 most active Atlantic hurricane seasons on record prior to 2020 averaged 20 tropical storms, 11 hurricanes, and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) of 186. The years that followed averaged 15 tropical storms, 7 hurricanes, and an ACE of 106. Those years that followed saw anywhere from below average activity to borderline hyperactivity. Is it possible that next year is also a very busy hurricane season? Certainly. But it’s almost equally likely that it could be a below average season if history is any guide. One of the best examples of this is the 2006 hurricane season. Preseason forecasts were very active, coming off the absurdly destructive 2005 season with high odds for both significant storms and impactful ones. What happened? We got 10 named storms and minimal U.S. impacts.

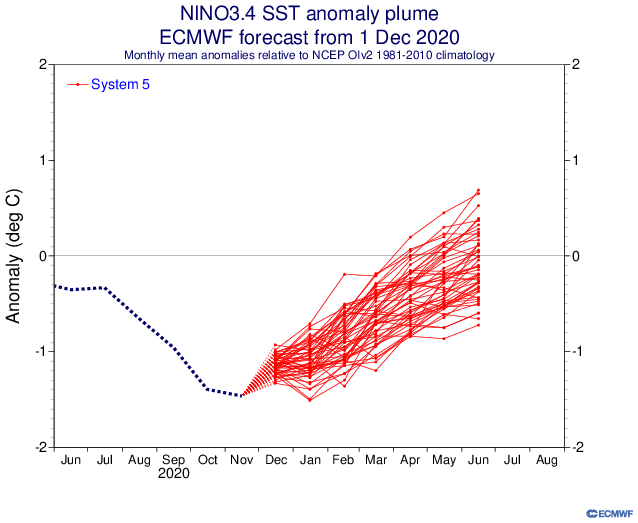

We can begin to take a very, very wild swing at what next season may setup as in terms of La Niña or El Niño (ENSO).

If we look at the CFS model from NOAA and the European (ECMWF) model, we can see their long-range forecasts for what “state” the tropical Pacific might be in several months down the road. Per the ECMWF model, while La Niña may be with us into spring, it looks to begin to perhaps fade toward May or June 2021.

As far as the CFS model goes, it shows basically the same idea: Weakening La Niña heading toward next summer.

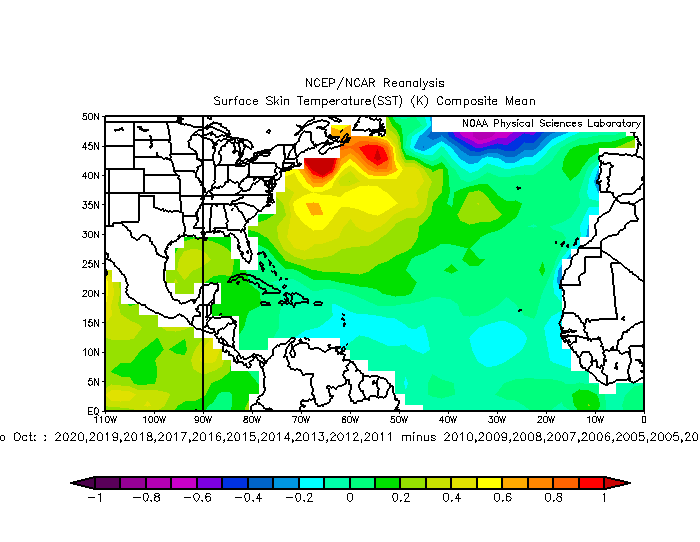

The huge caveat here is that these types of long-range forecasts of ENSO are notoriously fickle. A lot can and probably will change between now and next summer. However, the early read on things is that conditions may start the season in a borderline La Niña and then get less hospitable as the season wears on. There’s far more to consider besides ENSO, but those are mostly things we can’t really speculate on this far in advance. One thing we can at least look at are sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTs). Here’s a look at how SSTs have changed from 2001-2010 to 2011-2020.

Most of the Atlantic Basin has warmed during the peak months of August, September, and October, with the exception of some of the lower-latitudes between the Caribbean and Africa. This is likely due to both a combination of climate change and some cyclical background noise. Either way, it’s not a good thing.

If we want to expand further on climate change, we could talk about rapid intensification (RI), as climate change is likely leading to more RI and more significant RI. I went through a number of scientific papers on the subject recently. While there are still some mixed results about exactly which basins around the globe are more likely to see more RI and exactly how significant it will be, the general trend is pointing toward more of it in more storms. 2020 only furthered that concept.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season now has the most storms undergoing 36-hour intensification of at least 75, 80, 85, and 90kt pic.twitter.com/tiMBPTNa46

— Sam Lillo (@splillo) November 16, 2020

In the chart above, you can see how 2020 had the most storms with intensifications of 70 to 90 kts. in 36 hours of any prior modern hurricane season. Obviously with more storms, you should get more rapidly intensifying storms, but 2020 was sort of at some higher level than usual. And truthfully, it serves as another data point in a sea of them in recent years.

Putting all this together, you would probably expect next season to be near-average, maybe a little above, but nothing like 2020’s hurricane season. Still, if we are indeed moving into a world with more rapidly intensifying storms, it won’t take a large number of them in a hurricane season to cause problems, especially in the Gulf, as we witnessed with Hanna, Laura, Delta, and Zeta this year.

Thanks for the wrap up. Sadly it’ll take just one Cat 5 hitting the western tip of Galveston Island to cause massive flooding and destruction to the Houston area. I’m still sadden to see that all the homes on Virginia Point were wiped out when leaving Galveston. IR really scares me. By the time one knows one should go, it may be too late. While I’m thankful that my house didn’t flood with Harvey, by the time I thought we ought to leave, it was too late as too many roads were impassible. I fear a tropical storm forms close to the Houston area and spins up into a major hurricane in 24 hours or less.

Omg! Estabam, you are absolutely right about IR! I thought about it that regard before.

Thank you very much for your thoughtful analysis.